Simple Image Manipulations

Reading time: 17 mins.Review: a Simple Image Class

In the lesson on Reading and Writing Images, we wrote a very basic Image class. While very basic this design has already some interesting particularities. For example, we decided to represent the concept of pixel (or color if you prefer to look at it that way) with a structure named Rgb. The member variables of this structure are just three floats, each representing one the three primary colors of a pixel (red, green and blue).

struct Rgb

{

Rgb() : r(0), g(0), b(0) {}

Rgb(float c) : r(c), g(c), b(c) {}

Rgb(float _r, float _g, float _b) : r(_r), g(_g), b(_b) {}

float r, g, b;

};

To represent an image the resolution of this image and its pixel data are all we need. This is the minimum information required about an image in general. The resolution is defined by two integers, each representing the image width and height respectively (line 24). Pixels are defined as a flat array of Rgb elements dynamically allocated (line 25).

class Image

{

public:

struct Rgb {

Rgb() : r(0), g(0), b(0) {}

Rgb(float rr) : r(rr), g(rr), b(rr) {}

Rgb(float rr, float gg, float bb) : r(rr), g(gg), b(bb) {}

float r, g, b;

};

Image() : w(0), h(0), pixels(NULL) { /* empty image */ }

Image(const unsigned int &_w, const unsigned int &_h, const Rgb &c = kBlack) :

w(_w), h(_h), pixels(NULL)

{

pixels = new Rgb[w * h];

for (int i = 0; i < w * h; ++i)

pixels[i] = c;

}

const Rgb& operator [] (const unsigned int &i) const { return pixels[i]; }

Rgb& operator [] (const unsigned int &i) { return pixels[i]; }

~Image() { if (pixels != NULL) delete [] pixels; }

unsigned int w, h;

Rgb *pixels;

static const Rgb kBlack, kWhite, kRed, kGreen, kBlue;

};

// some default colors

const Image::Rgb Image::kBlack = Image::Rgb(0);

const Image::Rgb Image::kWhite = Image::Rgb(1);

const Image::Rgb Image::kRed = Image::Rgb(1,0,0);

const Image::Rgb Image::kGreen = Image::Rgb(0,1,0);

const Image::Rgb Image::kBlue = Image::Rgb(0,0,1);

It is generally more efficient to allocate one large block of memory holding all the pixels at once, rather than creating a two-dimensional array of pixels. There are two basic ways of implementing two-dimensional arrays: sequential arrays and arrays of arrays. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. In the case of sequential arrays, rows are laid out sequentially in memory. This provides simplicity in memory management and a slight speed advantage.

// allocating Rgb *pixels = nullotr; // allocating pixels = new Rgb[width* heigh]; // accessing Rgb pix = pixels[j * width + i]; //where j is the column index and i the row index // claiming memory back delete [] pixels

In the case of arrays of arrays, each element of a one-dimensional array is a pointer to another array. The disadvantage of this approach is that memory management is more complex, often requiring dynamic allocation and deallocation.

// allocating Rob *pixels = nullptr; // allocating pixels = new Rgb[width* heigh]; // accessing Rgb pix = pixels[j * width + i]; //where j is the column index and i the row index // claiming memory back delete [] pixels

For small arrays it's unlikely to make any difference! However for larger arrays the first option will be generally faster.

Finally there is two more interesting points to make about the implementation of our image class. First, we will use the bracket operator to access the pixels of an image rather than accessing the member variable directly. Technically, to be sure you can't access the member variables of the image class directly, you should make them private. This is generally desirable if you intend to package your code into an API, but if only used by you, this is not strictly necessary (this is your choice but our preference is to keep these member variables public to access them directly if needed which is often better for speed reasons):

const Rgb & pix = img.pixels[i]; // can now be written as: const Rgb & pix = img[i];

We also define in the class some default colors in the form of static constant member variables (line 26). Defining colors that way has its utility. It is not only provided as a conveniency. Consider this code:

const Rgb & pix = img[i];

if (pix != 0) {

... do something if pix is not black

}

We compare a pixel from the image to another pixel which is implicitly created. The 0 to the right of the inequality test, is implicitly converted into a Rgb structure. If executed many times, the cost of creating this structure each time would add up. Instead, we can write the following code:

const Rgb & pix = img[i];

if (pix != Image::kBlack) {

... do something if pix is not black

}

In this particular case, no variable is created because we test the pixel against one of the predefined color. While subtle, these micro-optimisations always pay off at the end when you have many of them in your code.

We also showed in the previous chapter how to read and write PPM images, allowing us to bring meaningful data in our program. However in its current version, we can't do much with these images. Let's see how we can extend this Image class to perform simple operations on these images.

Extending our Image Class: Simple Image Manipulations

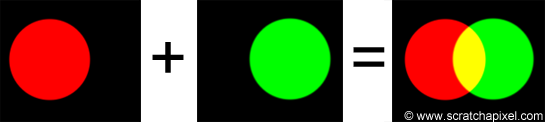

What do we mean by simple image manipulations? The type of manipulations we are thinking about for this lessons are for example adding two images or multiplying one image with another. Even though simple, we will see in the next chapter that we can already create some interesting effects with these simple operations. The following image shows what we get when we add or combine two images together:

We won't implement all the possible obvious options in this lesson (add, multiply, divide, subtract, etc.). If you need more operators, the few examples we provide should be enough for you to complete the implementation. One additional reason why this exercise is interesting is to show how easy some pretty complex operations can be reduced in C++ in just a few lines of code. How easy for instance would it be to express the addition of two images with the following code:

Image A, B; Image C = A + B;

Note: we will always assume that the two images have the same resolution. You can of course change the code to handle the case when they have a different size, but this makes the code more complex and supporting this feature has no educational value. This is left as an exercise for the reader.

This is actually very simple in C++, if we take advantage of the operator overloading mechanism. Let's see how this works:

Image operator + (const Image &img)

{

Image tmp(*this);

// add pixels to each other

for (int i = 0; i < w * h; ++i)

tmp[i] += img[i];

return tmp;

}

Keep in mind that because of the copy elision mechanism which is supported by most modern compilers, all copies involved in the process (the copy of the tmp image to the temporary variable returned by the function as well as the copy of this temporary variable to the variable itself) should be omitted. This point was discussed in detail in the previous lesson.

We need to return a new image which is the result of adding together the two images A and B involved in the addition. To make the code slightly more optimized, we start by using a copy constructor to initialize the returned image (tmp) with A. Because initializing an image involves allocating memory for the pixels, we need to define this copy constructor ourselves (we can't use the default one). Its implementation is straightforward:

// copy constructor

Image(const Image &img) : w(img.w), h(img.h), pixels(nullptr)

{

pixels = new Rgb[w * h];

memcpy(pixels, img.pixels, sizeof(Rgb) * w * h);

}

We initialize the width and the height of our new image with the width of the image of the image we want to copy over. Then we allocate the pixels for the new image and copy the pixels of the source image over. The temporary image is now intialized with the data of image A. To complete the task, we need to loop over the pixels of the image, and add to this temporary image the pixels values of the image B. Keep in mind that the bracket operator applied to an image is used to access pixels of an image (without accessing the pixels member variable from the Image class directly). This line:

tmp[i] += img[i]

implies that two pixels are added together. We make this possible by overloading the + operator of our Rgb structure itself (which is like a class):

Rgb& operator += (const Rgb &rgb)

{

r += rgb.r, g += rgb.g, b += rgb.b;

return *this;

}

And we are done. We can now express in code the addition of two images with a single + operator. Which leads to writing very simple and clean code. Here is the complete source of the image class to help you understand how all the bits that we added fit together:

class Image

{

public:

struct Rgb {

Rgb() : r(0), g(0), b(0) {}

Rgb(float c) : r(c), g(c), b(c) {}

Rgb(float _r, float _g, float _b) : r(_r), g(_g), b(_b) {}

Rgb& operator += (const Rgb &rgb) { r += rgb.r, g += rgb.g, b += rgb.b; return *this; }

float r, g, b;

};

Image() : w(0), h(0), pixels(NULL) { /* empty image */ }

Image(const unsigned int &_w, const unsigned int &_h, const Rgb &c = kBlack) :

w(_w), h(_h), pixels(NULL)

{

pixels = new Rgb[w * h];

for (int i = 0; i < w * h; ++i) pixels[i] = c;

}

// copy constructor

Image(const Image &img) : w(img.w), h(img.h), pixels(NULL)

{

pixels = new Rgb[w * h];

memcpy(pixels, img.pixels, sizeof(Rgb) * w * h);

}

// result = *this + img

Image operator + (const Image &img)

{

Image tmp(*this);

for (int i = 0; i < w * h; ++i)

tmp[i] += img[i];

return tmp;

}

const Rgb& operator [] (const unsigned int &i) const

{ return pixels[i]; }

Rgb& operator [] (const unsigned int &i)

{ return pixels[i]; }

~Image() { if (pixels != nullptr) delete [] pixels; }

unsigned int w, h;

Rgb *pixels;

static const Rgb kBlack, kWhite, kRed, kGreen, kBlue;

};

// some default colors

const Image::Rgb Image::kBlack = Image::Rgb(0);

const Image::Rgb Image::kWhite = Image::Rgb(1);

const Image::Rgb Image::kRed = Image::Rgb(1,0,0);

const Image::Rgb Image::kGreen = Image::Rgb(0,1,0);

const Image::Rgb Image::kBlue = Image::Rgb(0,0,1);

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try {

Image A = readPPM("...");

Image B = readPPM("...");

int w = A.w, h = A.h;

Image C(w, h); C = A + B;

}

catch (const std::exception &e) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: %s\n", e.what());

}

return 0;

}

Now that we found a way of adding two images together, let's implement a couple more operators following the same method. We will learn how to multiply and divide two images together. However, if the image on the right is filled with a constant color, all we need is multiply (or divide) the image on the left by a color.

The implementation of the multiplication operator is similar to the addition operator. All you need to do is duplicate the methods and replace the "+" sign by a "*" sign. To look into a slightly different case, we will consider the situation where the constant color is on the left of the multiplication sign, as in the following example:

Rgb ConstantColor(1, 0, 0); Image B = ConstantColor * A;

In this particular case, you need to precede the operator definition in the class with the C++ keyword friend. It makes it possible for the instance of the object on the left to access the member variables of the instance of the class on the right. You could very much avoid a friend method in the class by moving the constant color to the right of the multiplication sign. However this forces you to always write the multiplication in this order (with the image on the left and the color to the right). Here is the code for that operator:

friend Image operator * (const Rgb &rgb, const Image &img)

{

Image tmp(img);

tmp *= rub;

return tmp;

}

You will also need to change the Rgb structure and implement the multiplication compound assignment operator:

Rgb& operator *= (const Rgb &rgb)

{

r *= rgb.r, g *= rgb.g, b *= rgb.b;

return *this;

}

Let's now look at the divide operator. Again dividing two images together is trivial. Duplicate the code we used for the addition operator and replace the "+" sign with a "/" sign. In the following example we divide the image on the left by an image filled by a constant color (50% grey). Note that dividing the image by 0.5 is the same as multiplying it by 2 (which is the reason why the resulting image on the right is brighter).

Similarly, if we divide an image by a constant color, you can use the same approach than the one we have been using for the multiplication. Again, to look at a slightly different case, we consider the situation in which the compound division assignment operator is used, and the image divided by a float:

float div = 0.5; Image B /= div

The implementation of this operator in the Image class is straightforward. However, rather than adding a division operator in the Rgb structure, we can use the multiplication operator which is already implemented and multiply the pixels by the inverse of the divisor (one over the divisor).

Image& operator /= (const float &div)

{

float invDiv = 1 / div;

for (int i = 0; i < w * h; ++i)

pixels[i] *= invDiv;

return *this;

}

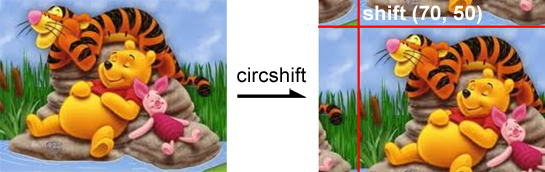

To conclude this lesson, let's implement a slightly more complicated image manipulation. We will be considering this case where we shift the image by some given amount of pixels to the right and to the bottom of the frame, however pixels which falling off at one end will be wrapped around in a circular fashion (they reappear on the opposite side). In other words, a pixel who position in x is greater than the image width, we reappear to the left of the frame (as in the example below).

Note that we will consider the case where the sift is positive both in x and y (implementing the case where either one of these values is negative is left as an exercise to the reader). We called this function circshift for a reason that will become clearer in the next chapter. However, as a hint, this function also exists in other languages such as Matlab and the literate programming language Octave.

Literate programs are written as an uninterrupted exposition of logic in an ordinary human language, much like the text of an essay, in which macros are included to hide abstractions and traditional source code.

We will implement this function as a static method of the Image class. Wrapping the pixels around can easily be achieve by taking the modulo of the shifted pixel coordinates with the image width or height (line 6 and 8):

static Image circshift(const Image &img, const std::pair &shift)

{

Image tmp(img.w, img.h);

int w = img.w, h = img.h;

for (int j = 0; j < h; ++j) {

int mod = (j + shift.second) % h;

for (int i = 0; i < w; ++i) {

int imod = (i + shift.first) % w;

tmp[jmod * w + imod] = img[j * w + i];

}

}

return tmp;

}

It can then be used this way:

Image A = Image::circshift(B, std::pair(i, j));

This will be the last example of image manipulation we will study in this lesson. Note how easy and simple it has become now to express more complex operations on images and colors by combining operators in a very literate way:

This will be the last example of image manipulation we will study in this lesson. Note how easy and simple it has become now to express more complex operations on images and colors by combining operators in a very literate way:

Image A = readPPM("...");

Image B = readPPM("...");

Image C(A.w, A.h);

C = Image::kRed * A + Image::circshift(B, std::pair(70, 50));

Image D = readPPM("...");

C += D

Exercise 1: display an image to the screen.

Exercise 2: implement the blending modes you can use in Photoshop to combine layers. A list of these blending modes with their mathematical formula can be found on Wikipedia.

Exercise 3: implement multithreading for image processing. Hint: look at the divide and conquer algorithm.

What Have We Learned?

We showed in this chapter how we could use advantage of the overloading operator mechanism in C++ to express operations on images such as addition, multiplication, division, etc. in a very easy and intuitive way. These operations can involve two images, an image and a constant color. The order in which these are defined doesn't matter. The color can either be to the left or to the right of the operator sign. If it appears to the left, you need to precede the definition of the operator with the keyword friend. We have even looked into the case where the image was divided by a single float. All this operations can also be implemented as compound assignment operators (such as +=, *=, /=, etc.). Because all these operations are defined with operators, we can easily combine them to create more complex manipulations and describe these manipulation in a literate fashion.

Source Code

The source code of this lesson (including the code from the following chapter) can be found in the laster chapter of this lesson.

The story of Marcie: it is worth writing a little bit about the story of the image that we are using in this lesson. This image which well known by professionals working in the film industry was created by Kodak. Officially, the image is known as the KODAK Digital LAD Test Image. According to Kodak:

The KODAK Digital LAD Test Image is a digital image that can be used as an aid in setting up digital film recorders to produce properly exposed digital negatives and in obtaining pleasing prints from those negatives.

Unofficially, in the industry, we generally refer to this image as "Marcie". And to answer all the questions of this fan "I'm wondering, who is this girl? Is "Marcie" really called Marcie? How old is she now? Is she still alive? Did she become a star model or actress?". She seems to be Marcy Rylan who indeed is an actress. The 32MB zipped original images in DPX format are available for download here. (c) Kodak.

What's Next?

Now that we learned about implementing some simple image manipulation in C++, in the next chapter we will show an example in which we will combine these operations to create an interesting effect, known as the bokeh effect. We intend to show than while simple on their own, we shouldn't underestimate what we can do with these operations by combining them together.