Generating Random Numbers

Reading time: 12 mins.The topic of random number generators is also related to the concept of noise generation. However, we won't be talking about noise in this lesson (noise as in the noise of the street, not the noise in your image produced by Monte Carlo methods). Check the lesson Value Noise and Procedural Patterns and Perlin Noise to learn about noise as a procedurally generated pattern.

Generating (Pseudo-)Random Numbers on a Computer

This chapter will be short. We don't intend, at least in this version of the lesson, to talk about the topic of random number generators in detail. However, because Monte Carlo methods rely mostly on being able to generate random numbers (often with a given PDF), it is really important to mention that having a good random number generator is important to guarantee the quality of the output of the Monte Carlo method. We will explain what a good random number generator is in a moment and explain briefly how these generators work.

Generating random numbers is a prerequisite to using any of the Monte Carlo methods in a computer program. So how do you generate random numbers? True random numbers (true as in unpredictable) can be generated with a computer! Imagine, for instance, a device that would measure a natural phenomenon that is itself random (such as the temperature of your CPU or the number of times you typed the letter 'a' on your keyboard in the last 10 seconds) and convert this measure to a digit that the computer can use as a random number. As random as these natural phenomena are, it is not hard to understand why such a device would be ideal for providing random numbers to a program. Besides being too slow for a computer, the main problem of such a system is that the random values we get from monitoring these "real world" random variables don't necessarily map appropriately to the type of random variable a computer program needs. As the Russian mathematician Ilya M. Sobol puts it:

A random variable that satisfactorily describes a physical quantity in one type of phenomenon may prove unsatisfactory when used to describe the same quantity in other phenomena.

Furthermore, the quality of the numbers produced by such a device would be hard to check. Finally, and maybe most importantly, it may be advantageous to "lock" the sequence of generated random numbers so that each time the program is run, the same numbers are produced in the same order. You might think, well, that's not random, then. They are deterministic, which sounds like the opposite of random. Indeed, and that is why we call such systems pseudorandom rather than random. They produce numbers that have the property of being randomly distributed, but their values and the order in which they are produced are always the same. In rendering, this property is critical. If you use Monte Carlo methods to create an image, a "repeatable" random number generator (it would be pseudorandom then) allows you to lock the noise pattern in the picture. "Repeatability" of the results in a production environment is a necessity (at least for studios like Pixar, it is). Thus, any random number generator that relies on a physical device (and they do exist, we will talk about them later in this chapter), however probably "truly random," is not always ideal. To summarize, "controllable and repeatable randomness" is generally what we are truly after.

Generally, you can use three approaches to get random numbers in a program. You can use pre-generated sequences of random numbers stored in tables (an old but very easy-to-implement method if one day you have to quickly write something of your own), and you can use a (true-)random number generator or a pseudorandom number generator.

Tables of Random Numbers

The principle is straightforward and similar to how lottery numbers are generated. If you write each number from 0 to 99 (say) on a card, put all the cards in a hat, shake it, and draw all the cards from this hat one by one, you end up with a sequence of 100 random numbers. To use these numbers in a program, you can store them in memory (in the same order in which they were picked from the hat) and create a global variable to keep track of the next random number that can be used from that table. This is simple, of course, but this approach has two difficulties. First, the sequence of numbers needs to be truly random (you don't shake the hat very well, and many of the numbers end up in increasing order). And it is hard to guarantee that the physical device used in generating these numbers, produces sequences with the desired probability distribution (you can use statistical tests to check whether your sequence of random numbers has some desired properties such for instance whether the numbers are truly independent and identically distributed or i.i.d.). Furthermore, the sequence of random numbers is limited in size.

short rand[100] = {16, 55, 30, 12, 3, 92, ... };

int counter = 0;

int N = 32;

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

short randNumber = rand[counter++];

...

}

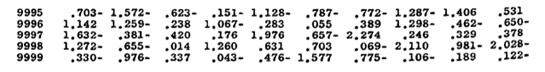

In 1955, Rand Corporation released a sequence of 1 million random digits. It is the longest sequence of random numbers ever published (look for "A MILLION Random Digits WITH 100,000 Normal Deviates", on the Rand Corporation website).

Abstract: not long after research began at RAND in 1946, the need arose for random numbers that could be used to solve problems of various kinds of experimental probability procedures. These applications, called Monte Carlo methods, required an ample supply of high-quality random digits and normal deviates, and the tables presented here were produced to meet those requirements. This book was a product of RAND's pioneering work in computing and a testament to the patience and persistence of researchers in the early days of RAND. The tables of random numbers in this book have become a standard reference in engineering and econometrics textbooks. In addition, they have been widely used in gaming and simulations that employ Monte Carlo trials. Still the most extensive published source of random digits and normal deviates, the work is routinely used by statisticians, physicists, poll takers, market analysts, lottery administrators, and quality control engineers.

(True-)Random Number Generator

As its name suggests, a random number generator produces truly random numbers (as in "you will never know what you will get" or, in more formal terms, the results are unpredictable). These are generally produced by physical devices, also known as noise generators, which are coupled with a computer. In computing, an apparatus that produces random numbers from a physical process is called a hardware random number generator or TRNG (for true random number generator).

As mentioned before, if "true" randomness is required, these generators are suitable, but they present some difficulties. First, as mentioned, noise is generated by a physical device (such as a vacuum diode), and the resulting analog signal needs to be converted somehow to a sequence of digits (a sequence of 0 and 1 which can then be interpreted as digits). This is a challenging task. Plus, these generators don't necessarily produce random numbers as quickly as the program needs them (or, put differently, it is hard to synchronize the calls of the program to the random number generator with the output of the hardware noise generator). They can also suffer from hardware failures, and the quality of the sequence they produce is hard to check (they can suffer from bias, which happens when they statistically create more 0s than 1s).

(Pseudo-)Random Number Generator

Anyone who considers arithmetical methods of producing random digits is in a state of sin. John von Neumann.

As long as the random numbers produced by a system can be checked by some tests that prove that they have the same "statistical" properties as a truly random variable (such as being uniformly distributed, for example), the mean by which these numbers are generated doesn't matter. Computers are deterministic, so producing truly random numbers with a computer is challenging, as we mentioned before, which is why we generally resort to using noise generators (which we talked about earlier on) if we need "true" randomness. However, what we can do on a computer, is develop some algorithm for generating a sequence of numbers that approximates the properties of random numbers. When numbers are produced by some algorithm or formula that simulates the values of a random variable X, they are called pseudorandom numbers. And the algorithm is called a pseudorandom number generator (or PRNG). The term "simulate" here is essential: it simply means that the algorithm can generate sequences of numbers that have similar statistical properties (and this can be tested) to that of the random variable we want to simulate. For instance, if we need to simulate a random variable X with probability distribution D, then we will need to test whether the sequence of numbers produced by our PRNG has the same distribution.

Before it gets too abstract, let's give a practical example of such a generator. One of the first PRNG algorithms was proposed by John von Neumann himself. It is called the middle-square method. This method is an example; don't use it in production. The idea is elementary. We start with a four-digit number such as \(n_0 = 0.4872\). If we square this number, we get the eight-digit number 0.69799713. If we now take out the middle four digits of this number, we get \(n_1 = 0.7997\). If we square this number, we get 0.89425947. Once again, we take out the middle four digits to find the next number in our sequence: \(n_2 = 0.4259\). If we keep repeating this process, again and again, we get the following sequence of numbers: \(n_0\) = 0.4872, \(n_1\) = 0.7997, \(n_2\) = 0.4259, \(n_3\) = 0.2610, \(n_4\) = 0.0881, \(n_5\) = 0.6816, etc. The following small program is a quick implementation of this algorithm (it only computes the first 10 "random numbers" of the sequence).

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

float seed = 0.4872, rand = seed;

int seqlength = 10;

while (seqlength--) {

printf("%0.4f\n", rand);

rand = sqrtf(rand);

rand = ((int)((rand * 100 - (int)(rand * 100)) * 10000)) / 10000.f;

}

return 0;

}

Again, this algorithm is too limited to be helpful. For example, the program doesn't work if the seed is 0. Better algorithms exist, and we will briefly talk about them in a moment. But for now, let's discuss the pros and cons of PRNG. In computing, pseudorandom generators are generally the preferred choice for people writing programs using Monte Carlo methods. First, a software solution is usually better than a hardware one because it's more reliable and easier to integrate into other programs. Because they can be programmed, they can generate sequences of random numbers in a predictable manner (and the statistical properties of these pseudorandom numbers are also predictable. They need to be checked only once which is not the case of numbers produced by noise generators). In other words, they are deterministic, which, as we explained before, is helpful in "locking" the output of a process based on a random number generator (which is the case of Monte Carlo ray tracing). PRNG algorithms are fast and fit in just a few lines of code. Note that all these algorithms can be seeded. In other words, you can initialize them with a number, and the sequence of resulting numbers depends on this seed.

The main disadvantage is that the sequences produced by this algorithm are periodic. Why? Because each number depends on the previous number in the sequence. We can write this as:

$$x_n = F(x_{n - 1}).$$The precision of any number in a computer's memory is limited by the number of bytes used to store this number. If the number of bytes is fixed, only a finite number of "numbers" can be generated. Therefore, it is expected that sooner or later, one of the generated numbers (let's call this number \(x_L\)) will coincide with one of the numbers already generated in the sequence (let's call this number \(x_N\)). The sequence period would then be L - N (the period is the number of values in the sequence before the sequence repeats itself). Should we care about this? The period of the C library function drand48() for example is \(2^{48}\ = 281474976710656\). This is a very big number, and some of the more recent generators have even longer periods, so unless the number of random numbers generated by your program exceeds this period (which is unlikely to happen), you shouldn't care.

Two of the most popular algorithms for PRNG are the Linear congruential generator on which the C library function drand48 is based and the Mersenne Twister algorithm (implemented in the "random" C++11 library - see below). We will explain how these algorithms work in a future revision of this lesson (and once all the lessons of the basic section are completed).

The C++11 Random Library

Knowing the function from the C/C++ libraries you can use to generate pseudorandom numbers is quite useful and important. You could only use functions such as drand48(). It produces (almost) uniformly distributed random numbers in the interval [0,1]. If you wanted to generate random numbers with any other distribution, you had to write your own!

Hopefully, the latest C++ standard (C++11) now comes with a random library. It provides a pseudorandom generator that is made of two parts. The first part is called the generator engine. It generates the numbers (you can choose among three different algorithms for generating these numbers), and the second part controls the distribution of the outcome (uniform, Poisson, normal, etc.).

#include <random> #include <functional> std::uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution(0, 99); std::mt19937 engine; //Mersenne twister MT19937 auto generator = std::bind(distribution, engine); int random = generator(); //Generate a uniform integral variate between 0 and 99. int random2 = distribution(engine); //Generate another sample directly using the distribution and the engine objects.