Monte Carlo Methods

Reading time: 15 mins.This lesson is complementary to the previous lesson 16\. The lesson Mathematical Foundations of Monte Carlo Methods is more about the concepts upon which Monte Carlo methods are built. In this lesson, we will talk about the methods themselves, and provide some practical examples.

Monte Carlo Methods: I Am Feeling (Un-)Lucky!

In rendering, the term Monte Carlo (often abbreviated as MC) is often used, read, or heard. But what does it mean? Now that you spent a fair amount of time reviewing the concept of statistics and probabilities, you will realize (it might come as a deception to certain) that what it refers to, is an incredibly simple idea. However simple, it is powerful and has some interesting properties that make it very attractive for solving various problems. In short, Monte Carlo methods refer to a series of statistical methods essentially used to find solutions to things such as computing the expected values of a function or integrating functions that can't be integrated analytically because they don't have a closed-form solution for example (see also the lesson The Mathematics of Shading). What we mean by statistical methods is that they use sampling techniques similar to those we studied in great detail in the last chapters to compute these solutions. Why do we say Monte Carlo methods? Simply because the same principle can be used to solve different problems and each one of these problems is associated with a different technique or algorithm. What all these algorithms have in common is their use of random (or stochastic) sampling. As described by Russian mathematician Sobol:

The Monte Carlo method is a numerical method of solving mathematical problems by random sampling (or by the simulation of random variables).

Monte Carlo (MC) methods all share the concept of using randomly drawn samples to compute a solution to a given problem. These problems generally come in two main categories:

-

Simulation: Monte Carlo or random sampling is used to run a simulation. If you want to compute the time it will take to go from point A to point B, given some conditions such as the chances that it will rain on your journey or that it will snow, the chances that there will be a traffic jam, that you will have to stop on your way to get some gas, etc. you can set these conditions at the start of your simulation and run the simulation 1,000 times to get an estimated time. As usual, the higher the number of runs or trials (here 1,000), the better your estimate.

-

Integration: this is a technique useful for mathematicians. In The Mathematics of Shading, we learned how to compute simple integrals using the Riemann sum technique. As simple as this can be, this approach can be quite computationally expensive as the dimension of the integral increases. MC integration though, while not having the greatest rate of convergence to the actual solution of the integral, can give us a way of getting a reasonably close result at a "cheaper" computational cost.

But let's rephrase this to emphasize something very important about this method (actually what's truly and fundamentally exciting and beautiful about it). If it is true that the more samples you use, the closer the MC method gets to the actual solution because we use random samples, an MC method can as well "just" randomly fall on the exact value by pure chance. In other words, on occasions, running a single MC simulation or integration will just give the right solution. However, on most occasions, it won't, but averaging these results will nevertheless converge to the exact solution anyway (we've learned about this and the Law of Large Numbers in Mathematical Foundations of Monte Carlo Methods).

For example, given some conditions about the weather and time of the week and day you will be traveling from A to B, our first simulation gives us the time of 1 hour and 32 minutes. Now let's say that none of the other 1,000,000,000,000 simulations we ran using the same conditions gave you that number, but when averaging their results though we get 1 hour and 32 minutes. In other words, your first simulation gave you what seems to be the actual solution to your problem (what you might expect the average of one trillion simulations to be pretty close to). Of course, you don't know that you get the right answer after only one trial, but this is one of the great characteristics of the method: with very few samples, sometimes, you may as well get the exact solution (or very close to it).

However in the strength of the MC methods also lies their main weakness. If by chance you sometimes get the right or close to the right solution with only a few samples, you may as well be unlucky at some other times and need a very large number of samples before getting close to the right answer. Generally, the rate of convergence of MC methods (the rate by which the MC methods converge to the right result as the number of samples increases) is pretty low (not to say poor). We will talk about this again further in this chapter. This is another important characteristic of the MC methods you need to remember.

Hit-or-Miss Monte Carlo Method

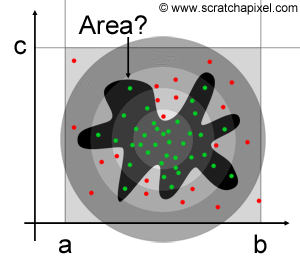

We will detail each technique (Monte Carlo simulation and integration) as well as provide an example of how MC methods are actually used in computer graphics and particularly in the field of rendering. However, before we get to this point, it is useful and easy to introduce the concept with a simple example. Imagine that we want to estimate the area of an arbitrary shape such as the one we drew in Figure 1. All we know is the area of the rectangle containing this shape and defined by the boundary ac and ab. Because these boundaries define a simple rectangle, we know the area of this rectangle to be \(A = ab \times ac\). To estimate the area of the shape itself, we can use a technique called hit-or-miss (also sometimes called the rejection method). The idea is to "throw" a certain number of random points uniformly into the rectangle and count the number of these points that are on the shape (hits) and reject the others. Because points are randomly distributed over the area of the rectangle \(ab \times ab\), it is reasonable to assume that the area of the shape is proportional to the number of hits over the total number of thrown points (in other words, the ratio of hits to the total number of samples is an approximation of the ratio of the area of the shape to the area of the rectangle in which the shape is inscribed). Assuming we keep the total number of samples (thrown points) constant: the bigger the shape, the higher the number of hits, and reciprocally, the smaller the shape the fewer hits. We can write:

$$A_{shape} \approx {N_{hits} \over N_{total} } \times A \text{ where } A = ab \times ac.$$

This is a very basic and simple example of how random sampling is used to solve a given problem (this device was originally developed by von Neumann himself who you can see in the photograph at the end of this chapter). A few things should be noted. Of course, the more samples we use, the better the estimate. It is also important to note that the distribution of samples over the area of the rectangle needs to be uniform. If for whatever reason more points were falling within a certain region of the rectangle (as in Figure 2 where the density of samples increases as we get to the center of the figure), then the result would be biased (that is, the result would be different than the true solution by some offset). We will see in the next lesson on importance sampling, that uniform sampling is not an absolute condition for using MC methods. When we know that a non-uniform distribution is used, we can compensate for the bias that it would normally introduce by some other method. Why would we be interested in using non-uniform sampling then? Because, as we will see in the next lesson on importance sampling, this can be used as a variance reduction technique. Variance, as explained in the previous lesson Mathematical Foundations of Monte Carlo Methods, is a measure of the error between our estimate and the true solution. The only brute-force and most obvious way by which variance can be reduced in MC methods are by increasing \(N\), the total number of samples. However, some other methods involving the way random samples are generated (see the chapter on Quasi or Pseudo-Random Numbers at the end of this lesson) and importance sampling (in which non-uniform sampling distributions are used) can also be used to reduce variance. However (and before we study these more advanced methods), keep in mind that basic or naive Monte Carlo methods require the samples to be uniformly distributed. Remember that a random number has a uniform distribution if all its possible outcomes have the same probability to occur (a property known as equiprobability).

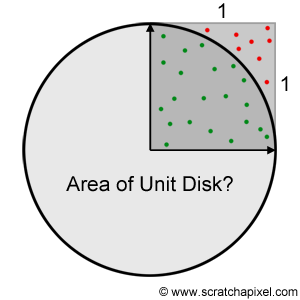

As a practical example, let's say we want to estimate the area of a unit disk using the hit-or-miss Monte Carlo method. We know the radius of the unit disk is 1 thus the unit circle is inscribed within a square of length 2. We could generate samples within this square and count the number of points falling within the disk. To test whether the point is inside (hit) or outside (miss) the disk, we simply need to measure the distance of the sample from the origin (the center of the unit disk) and check whether this distance is smaller (or equal) than the disk radius (which is equal to 1 for a unit disk). Note that because we can divide the disk into four equal sections (or quadrants) each inscribed in a unit square (Figure 3) we can limit this test to the unit square and multiply the resulting number by four. To compute the area of a quarter of the unit disk, we then simply divide the total number of hits (the green dots in Figure 3) by the total number of samples and multiply this ratio by the area of the unit square (which is equal to 1). The following C++ code implements this algorithm:

#include <cstdlib>

#include <cstdio>

#include <random>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

std::default_random_engine gen;

std::uniform_real_distribution<float> distr;

int N = (argc == 2) ? atoi(argv[1]) : 1024, hits = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

float x = distr(gen);

float y = distr(gen);

float l = sqrt(x * x + y * y);

if (l <= 1) hits++;

}

fprintf(stderr, "Area of unit disk: %f (%d)\n", float(hits) / N * 4, hits);

return 0;

}

This code uses the function from the random C++11 random library to generate random numbers using a given random number generator (more information on generating random numbers on a computer can be found in one of the next chapters of this lesson) and a given probability distribution (in this case, a uniform distribution). Check the documentation for more information on these C++11 libraries (C++11 is, by 2013, the most recent version of the standard of the C++ programming language). If you compile and run this program, you should get:

clang++ -o pi -O3 -std=c++11 -stdlib=libc++ pi.cpp ./pi 1000000 Area of unit disk: 3.141864 (785466)

You can update this example using the latest available version of C++ which in 2022, would be C++20.

As you can see, we get pretty close to the exact solution (which is \(\pi\) since the area of the unit disk is \(A = \pi r^2\) with \(r = 1\)), and as you increase the number of samples (which you can as an argument to the program), the estimate keeps getting closer to this number (as expected). If you used a 3D application in the past, you probably used random sampling already, maybe without knowing it. With this program though (and the next ones to follow) you can now actually say that you not only know what an MC method is but also implement a practical example of your own to illustrate such a method.

Why Do We Use Monte Carlo Methods?

If you run the code to compute the area of the unit disk, you will find that we need about 100 million samples to approximate the number \(\pi\) to its fourth decimal (3.1415). Is it an efficient way of estimating the number \(\pi\)? The answer is no. Then, why do we need Monte Carlo methods at all, if they don't seem that efficient? As already mentioned in previous lessons, we say that an equation has a closed-form solution when this solution can be expressed and thus computed analytically. However many equations do not have such closed-form solutions and even when they do, sometimes their complexity is such that they could only be solved given infinite time. Such problems or equations are said to be intractable. It's often better to have some predictions about the possible outcomes of a given problem, than not have any predictions at all. And Monte Carlo methods are then sometimes the only practical methods by which estimates of these equations or problems can be made. As Metropolis and Ulam put it in their seminal paper on the Monte Carlo Method (see reference section):

To calculate the probability of a successful outcome of a game of solitaire is a completely intractable task. [...] the practical procedure is to produce a large number of examples of any given game and then to examine the relative proportion of successes. [...] We can see at once that the estimate will never be confined within given limits with certainty, but only - if the number of trials is great - with great probability.

As we will see in the next chapters, many of these problems such as definite integrals can be efficiently solved by some numerical methods which are generally converging faster than MC methods (in other words, better methods). However, as the dimension of the integrals increase, these methods often become computationally expensive whereas the Monte Carlo ones can still provide a reasonably good estimate at a fixed computational cost (defined by the number of samples spared in computing estimations). For this reason, for complex integrals, MC methods are generally a better solution (despite their pretty bad convergence rate).

Finally, Monte Carlo methods are generally incredibly simple to implement and very versatile. They can be used to solve a very wild range of problems, in pretty much every possible imaginable field. In Metropolis and Ulam's paper, we can read:

The "solitaire" is meant here merely as an illustration for the whole class of combinatorial problems occurring in both pure mathematics and the applied sciences.

As already suggested in the introduction, Monte Carlo methods' popularity and development have very much to do with the advent of computing technology in the 1940s in which von Neumann (pictured above) was a pioneer. In a report on the Monte Carlo method published in 1957 by the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, we could already read:

The present state of development of high-speed digital, computers permits the use of samples of a size sufficiently large to ensure satisfactory accuracy in most practical problems.

This is important to understand because on its own while being a pretty simple idea, using MC without the help of a computer is a pretty tedious not to say an unusable approach to solving any sort of problem. A computer can execute all the calculations for us, which is why despite its poor convergence rate, Monte Carlo or stochastic sampling has become so popular. We just let computers do the tedious work for us.

Finally, let's conclude this chapter by saying that Monte Carlo methods have very much to do as well with the generation of random numbers (the first few chapters of this lesson were dedicated to studying random variables). To run an MC algorithm we first need to be able to generate random numbers (generally with a given probability distribution). For this reason, the development of algorithms for generating such "random" numbers (they appear random but generally they are not "truly" random which is why these algorithms are called pseudorandom number generator), has been an important field of research in computing technology. This topic will be further developed in one of the next chapters.

What's Next?

The rest of this lesson is focused on providing you with some practical examples of MC methods. The next chapter is focused on MC simulation. The one after that is devoted to MC integration. We will then explain how MC is used in computer graphics and rendering in particular (with a practical example). Finally, we will talk about the topic of generating random numbers on a computer, variance reduction methods, and Quasi-Monte Carlo (or QMC).

This work is provided to you for free and requires hours of work. If you find this content useful, please consider donating.