Creating a Simple 2D Noise

Reading time: 15 mins.We have explained most of the techniques used for creating noise in the previous chapter. Creating higher dimensional noise should be from now on much more straightforward task, as they are all based on the same concepts and techniques. Be sure to have mastered and truly understood what we described in the previous chapter before you move on. If things are not quite clear yet, read it again or drop us an email if you have questions.

Remember that all noise functions return a float but that its input can be a float, a 2D point, or a 3D point. The name given to the noise function is related to the dimension of its input value. A 2D noise is therefore a noise function that takes a 2D point as input. A 3D noise takes a 3D point, and we even mentioned a 4D noise in the first chapter of this lesson where the fourth dimension accounts, in fact for time (it will produce a noise pattern based on a 3D point but animated through time).

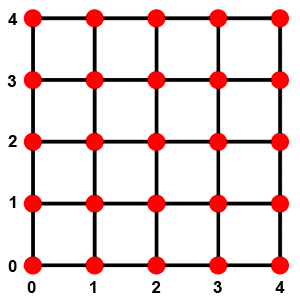

If you read the lesson on Interpolation (we suggest you do it now if you have not), you may already know how things work for 2D noise. For the 2D case, we will distribute random values at the vertex position of regular 2D grids (figure 1). The 2D version of the noise function will take a 2D point as input. Let's call this point P. Similarly to the 1D version, we will need to find the position of that point on the grid. Like the 1D case, our 2D grid has a predefined resolution (the grid is square, so the resolution is the same along the x and y-axis). Let's say 4 (which is a power of two) for the sake of this explanation. We will use the same modulo trick to remap the position of P on the grid if the point is outside the grid boundaries (if P's coordinates are lower than 0 or greater than 4). We will perform the modulo operation on P's x and y coordinates. That will give us new coordinates for the point on the grid (let's call this new point Pnoise).

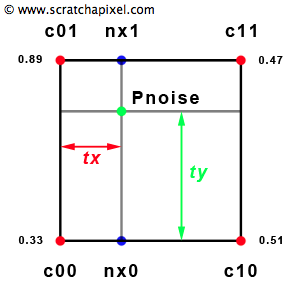

As you can see in Figures 2 and 3, the point is surrounded by the four vertices of a cell. We will use the same technique described in the lesson on interpolation to find a value for that point by linearly interpolating the values from the cell corners. To do this, we will first compute tx and ty, which are the counterpart of t in our 1D noise.

Using tx, we can now interpolate the values from the two corners on the left with the values from the two corners on the right. That would give us two values, nx0 and nx1, which correspond to the linear interpolation along the x-axis of c01/c10 (nx0) and c01/c11 (nx1). We now have two interpolated values on the lower and upper edge of the cell vertically aligned on Pnoise's x coordinate that we will linearly interpolate using ty. The result of this interpolation along the y-axis is our final noise value for P.

Here is the code of our simple 2D value noise. The size of the grid is 256 on each side. Note that, like for the 1D noise, it is possible to change the remapping function for t. In this version, we have chosen the Smoothstep function. Still, you could experiment by ignoring the function (using tx and ty directly), using the Cosine smooth function, or any alternative smooth function you know about.

#include <cstdio>

#include <random>

#include <functional>

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <cmath>

template<typename T>

class Vec2

{

public:

Vec2() : x(T(0)), y(T(0)) {}

Vec2(T xx, T yy) : x(xx), y(yy) {}

Vec2 operator * (const T &r) const { return Vec2(x * r, y * r); }

T x, y;

};

typedef Vec2<float> Vec2f;

template<typename T = float>

inline T lerp(const T &lo, const T &hi, const T &t)

{ return lo * (1 - t) + hi * t; }

inline

float smoothstep(const float &t) { return t * t * (3 - 2 * t); }

class ValueNoise

{

public:

ValueNoise(unsigned seed = 2016)

{

std::mt19937 gen(seed);

std::uniform_real_distribution<float> distrFloat;

auto randFloat = std::bind(distrFloat, gen);

// create an array of random values

for (unsigned k = 0; k < kMaxTableSize * kMaxTableSize; ++k) {

r[k] = randFloat();

}

}

float eval(Vec2f &p) const

{

int xi = std::floor(p.x);

int yi = std::floor(p.y);

float tx = p.x - xi;

float ty = p.y - yi;

int rx0 = xi & kMaxTableSizeMask;

int rx1 = (rx0 + 1) & kMaxTableSizeMask;

int ry0 = yi & kMaxTableSizeMask;

int ry1 = (ry0 + 1) & kMaxTableSizeMask;

// random values at the corners of the cell using the permutation table

const float & c00 = r[ry0 * kMaxVerticesMask + rx0];

const float & c10 = r[ry0 * kMaxVerticesMask + rx1];

const float & c01 = r[ry1 * kMaxVerticesMask + rx0];

const float & c11 = r[ry1 * kMaxVerticesMask + rx1];

// remapping of tx and ty using the Smoothstep function

float sx = smoothstep(tx);

float sy = smoothstep(ty);

// linearly interpolate values along the x axis

float nx0 = lerp(c00, c10, sx);

float nx1 = lerp(c01, c11, sx);

// linearly interpolate the nx0/nx1 along they y axis

return lerp(nx0, nx1, sy);

}

static const unsigned kMaxTableSize = 256;

static const unsigned kMaxTableSizeMask = kMaxTableSize - 1;

float r[kMaxTableSize * kMaxTableSize];

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

unsigned imageWidth = 512;

unsigned imageHeight = 512;

float *noiseMap = new float[imageWidth * imageHeight];

// generate value noise

ValueNoise noise;

float frequency = 0.05f;

for (unsigned j = 0; j < imageHeight; ++j) {

for (unsigned i = 0; i < imageWidth; ++i) {

// generate a float in the range [0:1]

noiseMap[j * imageWidth + i] = noise.eval(Vec2f(i, j) * frequency);

}

}

// output noise map to PPM

std::ofstream ofs;

ofs.open("./noise.ppm", std::ios::out | std::ios::binary);

ofs << "P6\n" << imageWidth << " " << imageHeight << "\n255\n";

for (unsigned k = 0; k < imageWidth * imageHeight; ++k) {

unsigned char n = static_cast<unsigned char="">(noiseMap[k] * 255);

ofs << n << n << n;

}

ofs.close();

delete[] noiseMap;

return 0;

}

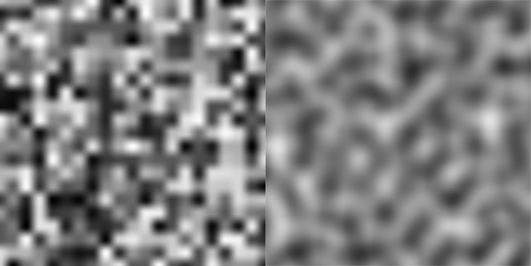

Figure 4 shows the result of this program.

Note that the result is probably not as good as we had hoped. The resulting noise is quite blocky. Noise from professional applications produces much smoother results. Remember that this lesson's goal is to teach you the basic concepts the noise function is built upon. We will need to use more elaborate techniques to improve the results, but studying them will be challenging unless you can make a simple function first. Don't worry too much about the result of the noise function for now, and try to grasp how it works and learn and understand its properties. You can still have fun playing around with this code and creating some interesting effects/images, as we will see in the next chapter. The next lesson will teach you about making a better-looking noise (part 2).

3D Noise and Beyond

This lesson will give an example of 1D and 2D noise. We will provide code for 3D and 4D noise in the next lesson on noise. However, if you read the lesson on interpolation and understood the concept explained in this chapter, you can easily extend the code to write a 3D noise. All you need to do is to interpolate the random values along the x-axis (resulting in 4 values) and the result of this interpolation along the y-axis (2 values). You will be left with two values that you will need to interpolate along the third dimension (the z-axis) to get a final result (the second lesson on noise contains an example of 3D noise).

Now there is a problem with our current code. We mentioned in the first chapter that noise was a compact function that didn't use a lot of memory. However, in the 2D case, we already have an allocated 256x256 array of random values. If we use the same technique for the 3D version, we will need to allocate a 256x256x256 array of floats which starts to be quite a significant chunk of memory for a function that is supposed to use very little of it. Ken Perlin solved this problem with a simple and elegant solution in the form of a permutation table which we will explain now.

Introducing the Concept of Permutation

Assuming we want the noise function to stay memory efficient, we will limit ourselves to using an array of 256 random values to compute our noise, whether we deal with the 1D, 2D, or 3D version of the function. To deal with this limitation, we must be sure that any input value to the noise function (a float, a 2D or 3D point) can map to one and only one value in this array of random values. As you already know, each input point coordinates to our noise function is converted into an integer. And this integer is used to look up the array of random values. Ken Perlin stored the numbers 0 to 255 in an additional array of 256 integers and shuffled (permuted) the entries of this array, randomly swapping each one. Perlin extended the size of this array to 512 and copied the values for the indices in the range 0 to 255 to the indices 256 to 511. In other words, copy the array's first half into the second half.

std::mt19937 gen(seed);

std::uniform_real_distribution<float> distrFloat;

auto randFloat = std::bind(distrFloat, gen);

// create an array of random values and initialize the permutation table

for (unsigned k = 0; k < kMaxTableSize; ++k) {

r[k] = randFloat();

permutationTable[k] = k;

}

// shuffle values of the permutation table

std::uniform_int_distribution<unsigned> distrUInt;

auto randUInt = std::bind(distrUInt, gen);

for (unsigned k = 0; k < kMaxTableSize; ++k) {

unsigned i = randUInt() & kMaxTableSizeMask;

std::swap(permutationTable[k], permutationTable[i]);

permutationTable[k + kMaxTableSize] = permutationTable[k];

}

Instead of directly looking up into the array of random values, we will first do a lookup using our integer position into this permutation array. As we know, the integer value for our input point is necessarily a multiple of 255. Let's say that this number is 201. Using this value to look up the permutation array will return the value stored in the table at index position 201. This lookup results in an integer in the range of 0-255, which we can now use as an index in the array of random values.

You may wonder why the permutation array is twice the size of the function period (512 in size instead of 256). If we deal with a 2D noise, we will first do a lookup in the permutation table using the integer value for the x coordinate of our input point (as described). This will return an integer value in the range [0:255]. We will add the result of this lookup to the integer value for the input point y coordinate and again use the sum of these two numbers as an index of the permutation table. Since the result of the first permutation lookup is in the range [0:255] and the integer value for the point's y coordinate is also in the range [0:255], it means that the range of possible index value for the permutation table is [0:511]. Hence the size of the permutation array (512). This code might help to clear things up for you:

int xi = std::floor(p.x); int yi = std::floor(p.y); float tx = p.x - xi; float ty = p.y - yi; int rx0 = xi & kMaxTableSizeMask; int rx1 = (rx0 + 1) & kMaxTableSizeMask; int ry0 = yi & kMaxTableSizeMask; int ry1 = (ry0 + 1) & kMaxTableSizeMask; // random values at the corners of the cell using the permutation table const float & c00 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx0] + ry0]]; const float & c10 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx1] + ry0]]; const float & c01 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx0] + ry1]]; const float & c11 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx1] + ry1]];

This technique is neat because it continues to work as you add more dimensions to your noise function. It provides a method to map any input point to a unique location in the random value array. All we do is use the input point's coordinates as indices of the permutation table. In programming, we call this technique a hash table or hash function. These techniques were quite popular at the time (and still are but are not as well known by the younger developers). They help map a particular key (a point location, for example) to some data stored in a memory block, making the lookup process efficient (check the lesson on programming techniques to learn more about hash functions).

Here is finally the latest memory-efficient version of our 2D noise function using the permutation table:

#include <cstdio>

#include <random>

#include <functional>

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <cmath>

template<typename T>

class Vec2

{

public:

Vec2() : x(T(0)), y(T(0)) {}

Vec2(T xx, T yy) : x(xx), y(yy) {}

Vec2 operator * (const T &r) const { return Vec2(x * r, y * r); }

T x, y;

};

typedef Vec2<float> Vec2f;

template<typename T = float>

inline T lerp(const T &lo, const T &hi, const T &t)

{ return lo * (1 - t) + hi * t; }

inline

float smoothstep(const float &t) { return t * t * (3 - 2 * t); }

class ValueNoise

{

public:

ValueNoise(unsigned seed = 2016)

{

std::mt19937 gen(seed);

std::uniform_real_distribution<float> distrFloat;

auto randFloat = std::bind(distrFloat, gen);

// create an array of random values and initialize the permutation table

for (unsigned k = 0; k < kMaxTableSize; ++k) {

r[k] = randFloat();

permutationTable[k] = k;

}

// shuffle values of the permutation table

std::uniform_int_distribution<unsigned> distrUInt;

auto randUInt = std::bind(distrUInt, gen);

for (unsigned k = 0; k < kMaxTableSize; ++k) {

unsigned i = randUInt() & kMaxTableSizeMask;

std::swap(permutationTable[k], permutationTable[i]);

permutationTable[k + kMaxTableSize] = permutationTable[k];

}

}

float eval(Vec2f &p) const

{

int xi = std::floor(p.x);

int yi = std::floor(p.y);

float tx = p.x - xi;

float ty = p.y - yi;

int rx0 = xi & kMaxTableSizeMask;

int rx1 = (rx0 + 1) & kMaxTableSizeMask;

int ry0 = yi & kMaxTableSizeMask;

int ry1 = (ry0 + 1) & kMaxTableSizeMask;

// random values at the corners of the cell using the permutation table

const float & c00 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx0] + ry0]];

const float & c10 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx1] + ry0]];

const float & c01 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx0] + ry1]];

const float & c11 = r[permutationTable[permutationTable[rx1] + ry1]];

// remapping of tx and ty using the Smoothstep function

float sx = smoothstep(tx);

float sy = smoothstep(ty);

// linearly interpolate values along the x axis

float nx0 = lerp(c00, c10, sx);

float nx1 = lerp(c01, c11, sx);

// linearly interpolate the nx0/nx1 along they y axis

return lerp(nx0, nx1, sy);

}

static const unsigned kMaxTableSize = 256;

static const unsigned kMaxTableSizeMask = kMaxTableSize - 1;

float r[kMaxTableSize];

unsigned permutationTable[kMaxTableSize * 2];

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

unsigned imageWidth = 512;

unsigned imageHeight = 512;

float *noiseMap = new float[imageWidth * imageHeight];

#if 0

// generate white noise

unsigned seed = 2016;

std::mt19937 gen(seed);

std::uniform_real_distribution<float> distr;

auto dice = std::bind(distr, gen); //std::function<float()>

for (unsigned j = 0; j < imageHeight; ++j) {

for (unsigned i = 0; i < imageWidth; ++i) {

// generate a float in the range [0:1]

noiseMap[j * imageWidth + i] = dice();

}

}

#else

// generate value noise

ValueNoise noise;

float frequency = 0.05f;

for (unsigned j = 0; j < imageHeight; ++j) {

for (unsigned i = 0; i < imageWidth; ++i) {

// generate a float in the range [0:1]

noiseMap[j * imageWidth + i] = noise.eval(Vec2f(i, j) * frequency);

}

}

#endif

// output noise map to PPM

std::ofstream ofs;

ofs.open("./noise.ppm", std::ios::out | std::ios::binary);

ofs << "P6\n" << imageWidth << " " << imageHeight << "\n255\n";

for (unsigned k = 0; k < imageWidth * imageHeight; ++k) {

unsigned char n = static_cast<unsigned char="">(noiseMap[k] * 255);

ofs << n << n << n;

}

ofs.close();

delete[] noiseMap;

return 0;

}