Implementing a Virtual Pinhole Camera

Reading time: 22 mins.Implementing a Virtual Pinhole Camera Model

In the last three chapters, we have explored everything there is to know about the pinhole camera model. This model is the simplest to simulate in computer graphics (CG) and is the most commonly used by video games and 3D applications. As mentioned briefly in the first chapter, pinhole cameras, by design, can only produce sharp images (without any depth of field). Although simple and easy to implement, this model is often criticized for its inability to simulate visual effects such as depth of field or lens flare. While some consider these effects to be visual artifacts, they significantly contribute to the aesthetic experiences of photographs and films. Simulating these effects is relatively straightforward (as it fundamentally relies on well-known and basic optical principles) but very resource-intensive, especially when compared to rendering an image with a basic pinhole camera model. We will introduce a method for simulating depth of field in another lesson, which, although resource-intensive, is less so than simulating depth of field by tracing the path of light rays through a camera lens's various optics.

In this chapter, we will apply everything learned in the previous chapters about the pinhole camera model and write a program to implement this model. Our goal is to demonstrate that this model works and to dispel any notions of mystery or magic about how images are produced in software such as Maya. By producing a series of images—altering different camera parameters in both Maya and our program, and comparing the results—we aim to show that, when the camera settings align, the images produced by the two applications should also match. Let's begin.

Implementing an Ideal Pinhole Camera Model

Throughout the rest of this chapter, when we discuss the pinhole camera, we will refer to the terms "focal length" and "film size." It's important to differentiate these from "near-clipping plane" and "canvas size," which are terms applicable only to the virtual camera model. However, there is a relationship between them. Let's revisit and clarify this relationship.

For the pinhole and virtual cameras to produce the same image, they must share the same viewing frustum. The viewing frustum is determined by two parameters: the point of convergence (the camera or eye origin—these terms refer to the same point) and the angle of view. We have also learned from previous chapters that the angle of view is determined by the film size and the focal length, two parameters specific to the pinhole camera.

Where Shall the Canvas/Screen Be?

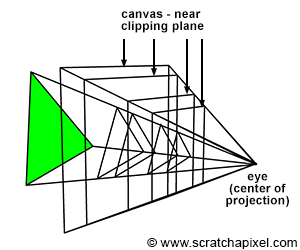

In computer graphics (CG), once the viewing frustum is defined, we then need to decide where the virtual image plane will be. Mathematically, the canvas can be positioned anywhere along the line of sight, as long as the surface onto which we project the image is contained within the viewing frustum, as illustrated in Figure 1. It can be located anywhere between the apex of the pyramid (obviously not at the apex itself) and its base (defined by the far clipping plane), or even beyond, if desired.

Do not confuse the distance between the eye (the center of projection) and the canvas with the focal length. They are not the same. The position of the canvas does not define how wide or narrow the viewing frustum is (neither does the near clipping plane); the shape of the viewing frustum is solely determined by the focal length and the film size. The combination of both parameters defines the angle of view and thus the magnification at the image plane. As for the near-clipping plane, it is merely an arbitrary plane which, along with the far-clipping plane, is used to "clip" geometry along the camera's local z-axis and remap points' z-coordinates to the range [0,1]. The rationale and methodology behind the remapping are explained in the lesson on the REYES algorithm, a popular rasterization algorithm, with the next lesson devoted to the perspective projection matrix.

Choosing the distance between the eye and the image plane to be equal to 1 is convenient because it simplifies the equations for computing the coordinates of a point projected on the canvas. However, opting for this convenience means missing out on exploring the generic (and slightly more complex) case where the distance to the canvas is arbitrary. Given our goal on Scratchapixel is to understand how things work rather than opting for simplicity, let's pursue the generic case. For now, we have decided to position the canvas at the near-clipping plane. This decision should not be overanalyzed; it is motivated purely by pedagogical reasons. Positioning the image plane at the near-clipping plane allows us to explore the equations for projecting points onto a canvas at an arbitrary distance from the eye. This choice also coincides with the perspective projection matrix's operation, which implicitly positions the image plane at the near-clipping plane, thereby setting the stage for what we will explore in the next lesson. However, it is important to remember that the positioning of the canvas does not influence the output image. Even if the image plane is located between the eye and the near-clipping plane, objects situated between these points can still be projected onto the image plane, with the equations for the perspective matrix remaining valid.

What Will Our Program Do

In this lesson, we will create a program to generate a wireframe image of a 3D object by projecting the object's vertices onto the image plane. This program will be very similar to the one we developed in the previous lesson; however, we will now extend the code to incorporate the concepts of focal length and film size. Generally, film formats are rectangular, not square, meaning our program will also produce images with a rectangular shape. Recall that in Chapter 2, we discussed how the resolution gate aspect ratio, also referred to as the device aspect ratio (the image width divided by its height), does not necessarily match the film gate aspect ratio (the film width divided by its height). In the final part of this chapter, we will additionally write some code to manage this scenario.

Here is a list of the parameters our pinhole camera model will require:

Intrinsic Parameters

-

Focal Length (Type: float)

-

Defines the distance between the eye (the camera position) and the image plane in a pinhole camera. This parameter is crucial for calculating the angle of view (Chapter 2). It's important not to confuse the focal length, which is used to determine the angle of view, with the distance to the virtual camera's image plane, which is positioned at the near clipping plane. In Maya, this value is expressed in millimeters (mm).

-

-

Camera Aperture (Type: 2 floats)

-

Determines the physical dimensions of the film used in a real camera. This value is essential for determining the angle of view and also defines the film gate aspect ratio (Chapter 2). The physical sizes of the most common film formats, generally in inches, can be found in this Wikipedia article (in Maya, this parameter can be specified either in inches or mm).

-

-

Clipping Planes (Type: 2 floats)

-

The near and far clipping planes are imaginary planes located at specific distances from the camera along the camera's line of sight. Only objects located between the camera's two clipping planes are rendered in the camera's view. Our pinhole camera model positions the canvas at the near-clipping plane (Chapter 3). It's crucial to differentiate the near-clipping plane from the focal length (see the remark above).

-

-

Image Size (Type: 2 integers)

-

Specifies the output image's size in pixels. The image size also determines the resolution gate aspect ratio (Chapter 2).

-

-

Fit Resolution Gate (Type: enum)

-

An advanced option used in Maya to define the strategy when the resolution aspect ratio differs from the film gate aspect ratio (Chapter 2).

-

Extrinsic Parameters

-

Camera to World (Type: 4x4 matrix)

-

Defines the camera position and orientation through the camera to world transformation (Chapter 3).

-

We will also need the following parameters, which we can compute from the parameters listed above:

-

Angle of View (Type: float)

-

Computed from the focal length and the film size parameters, this represents the visual extent of the scene captured by the camera.

-

-

Canvas/Screen Window (Type: 4 floats)

-

These represent the coordinates of the "canvas" (referred to as the "screen window" in RenderMan specifications) on the image plane, calculated from the canvas size and the film gate aspect ratio.

-

-

Film Gate Aspect Ratio (Type: float)

-

This is the ratio of the film width to the film height, determining the shape of the image captured by the camera.

-

-

Resolution Gate Aspect Ratio (Type: float)

-

The ratio between the image width and its height (in pixels), affecting how the final image will be displayed or projected.

-

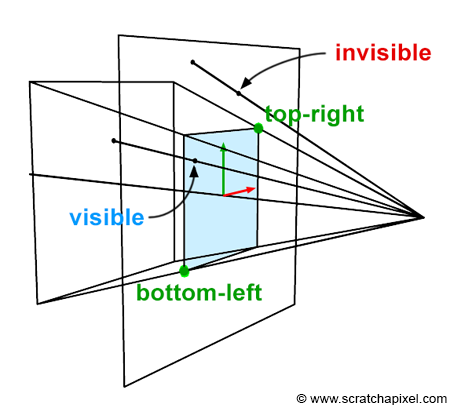

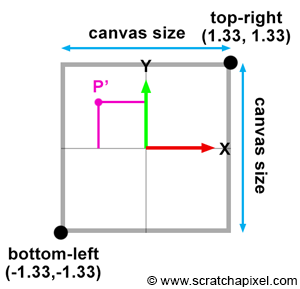

Remember that when a 3D point is projected onto the image plane, we need to test the projected point's x- and y-coordinates against the canvas coordinates to determine if the point is visible in the camera's view. Of course, the point can only be visible if it lies within the canvas limits. We already know how to compute the projected point coordinates using perspective divide. But we still need to know the canvas's bottom-left and top-right coordinates (Figure 2). So, how do we find these coordinates?

In almost every case, we want the canvas to be centered around the canvas coordinate system origin (Figures 2, 3, and 4). However, this is not always necessary or the case. For example, a stereo camera setup may require the canvas to be slightly shifted to the left or the right of the coordinate system origin. Therefore, in this lesson, we will always assume that the canvas is centered on the image plane coordinate system origin.

Computing the canvas or screen window coordinates is straightforward. Since the canvas is centered around the screen coordinate system origin, their values are equal to half the canvas size. They are negative if they are either below or to the left of the y-axis and x-axis of the screen coordinate system, respectively (Figure 4). The canvas size depends on the angle of view and the near-clipping plane (since we decided to position the image plane at the near-clipping plane). The angle of view is determined by the film size and the focal length. Let's compute each one of these variables.

Note, though, that the film format is more often rectangular than square, as mentioned several times. Thus, the angular horizontal and vertical extents of the viewing frustum are different. Therefore, we will need the horizontal angle of view to compute the left and right coordinates and the vertical angle of view to compute the bottom and top coordinates.

Computing the Canvas Coordinates: The Long Way

Let's start with the horizontal angle of view. In the previous chapters, we introduced the equation to compute the angle of view using trigonometric identities. If you observe the camera setup from the top, you'll notice that we can outline a right triangle (Figure 6). The adjacent and opposite sides of the triangle are known: they correspond to the focal length and half of the film's horizontal aperture. However, to use these in a trigonometric identity, they must be defined in the same unit. Typically, film gate dimensions are defined in inches, and focal length is defined in millimeters. Usually, inches are converted into millimeters, but you can convert millimeters into inches if you prefer; the result will be the same. One inch is equivalent to 25.4 millimeters. To find the horizontal angle of view, we will use a trigonometric identity that states that the tangent of an angle is the ratio of the length of the opposite side to the length of the adjacent side (equation 1):

$$ \begin{align*} \tan\left(\dfrac{\theta_H}{2}\right) &= \dfrac{A}{B} \\ &= \color{red}{\dfrac{ \left( \text{Film Aperture Width} \times 25.4 \right) / 2 }{ \text{Focal Length} }}. \end{align*} $$Where \(\theta_H\) is the horizontal angle of view. Now that we have \(\theta_H\), we can compute the canvas size. We know it depends on the angle of view and the near-clipping plane (because the canvas is positioned at the near-clipping plane). We will use the same trigonometric identity (Figure 6) to compute the canvas size (equation 2):

$$ \begin{array}{l} \tan(\dfrac{\theta_H}{2}) = \dfrac{A}{B} = \dfrac{\dfrac{\text{Canvas Width} } { 2 } } { Z_{near} }, \\ \dfrac{\text{Canvas Width} } { 2 } = \tan(\dfrac{\theta_H}{2}) \times Z_{near},\\ \text{Canvas Width}= 2 \times \color{red}{\tan(\dfrac{\theta_H}{2})} \times Z_{near}. \end{array} $$If we want to avoid computing the trigonometric function tan(), we can substitute the function on the right-hand side of equation 1:

To compute the right coordinate, we simply divide the whole equation by 2:

$$ \begin{array}{l} \text{right} = \color{red}{\dfrac {\dfrac { (\text{Film Aperture Width} \times 25.4) } { 2 } } { \text{Focal Length} }} \times Z_{near}. \end{array} $$Computing the left coordinate is straightforward. For example, here is a code snippet to compute the left and right coordinates:

float focalLength = 35; // 35mm Full Aperture

float filmApertureWidth = 0.980;

float filmApertureHeight = 0.735;

static const float inchToMm = 25.4;

float nearClippingPlane = 0.1;

float farClippingPlane = 1000;

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

#if 0

// First method: Compute the horizontal angle of view first

float angleOfViewHorizontal = 2 * atan((filmApertureWidth * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength);

float right = tan(angleOfViewHorizontal / 2) * nearClippingPlane;

#else

// Second method: Compute the right coordinate directly

float right = ((filmApertureWidth * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength) * nearClippingPlane;

#endif

float left = -right;

printf("Screen window left/right coordinates: %f %f\n", left, right);

...

}

We can use the same technique to compute the top and bottom coordinates, this time needing to compute the vertical angle of view (\(\theta_V\)):

$$ \tan({\theta_V \over 2}) = {A \over B} = \color{red}{\dfrac {\dfrac { (\text{Film Aperture Height} \times 25.4) } { 2 } } { \text{Focal Length} }}. $$From this, we can derive the equation for the top coordinate:

$$ \text{top} = \color{red}{\dfrac {\dfrac { (\text{Film Aperture Height} \times 25.4) } { 2 } } { \text{Focal Length} }} \times Z_{near}. $$Here is the code to compute all four coordinates:

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

#if 0

// First method: Compute the horizontal and vertical angles of view first

float angleOfViewHorizontal = 2 * atan((filmApertureWidth * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength);

float right = tan(angleOfViewHorizontal / 2) * nearClippingPlane;

float angleOfViewVertical = 2 * atan((filmApertureHeight * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength);

float top = tan(angleOfViewVertical / 2) * nearClippingPlane;

#else

// Second method: Compute the right and top coordinates directly

float right = ((filmApertureWidth * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength) * nearClippingPlane;

float top = ((filmApertureHeight * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength) * nearClippingPlane;

#endif

float left = -right;

float bottom = -top;

printf("Screen window bottom-left, top-right coordinates %f %f %f %f\n", bottom, left, top, right);

...

}

Computing the Canvas Coordinates: The Quick Way

The code we wrote works just fine. However, there's a slightly faster method of computing the canvas coordinates, which is often used in production code. This method involves computing the vertical angle of view to get the bottom-top coordinates, and then multiplying these coordinates by the film aspect ratio. Given that:

$$ \text{top} = \color{red}{\dfrac {\dfrac { (\text{Film Aperture Height} \times 25.4) } { 2 } } { \text{Focal Length} }} \times Z_{near} $$This formula calculates the top boundary of the camera's view at the near clipping plane, based on the Film Aperture Height, the focal length, and the distance to the near clipping plane (\(Z_{near}\)). The \(25.4\) factor converts inches to millimeters, assuming the Film Aperture dimensions are provided in inches.

To find the right boundary using the aspect ratio (which is Film Aperture Width / Film Aperture Height), we can substitute the calculation for top into the equation for right:

Substituting the given formula for top:

Given this substitution, the right calculation appears as:

Simplifying further:

$$ \text{right} = \dfrac {\dfrac { (\text{Film Aperture Width} \times 25.4) } { 2 } } { \text{Focal Length} } \times Z_{near} $$The following code demonstrates how to implement this solution:

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

float top = ((filmApertureHeight * inchToMm / 2) / focalLength) * nearClippingPlane;

float bottom = -top;

float filmAspectRatio = filmApertureWidth / filmApertureHeight;

float right = top * filmAspectRatio;

float left = -right;

printf("Screen window bottom-left, top-right coordinates %f %f %f %f\n", bottom, left, top, right);

...

}

Does it Work? Checking the Code

Before we test the code, we need to make a slight change to the function that projects points onto the image plane. Remember that to compute the projected point coordinates, we use a property of similar triangles. For example, if \(A\), \(B\), \(A'\), and \(B'\) are the opposite and adjacent sides of two similar triangles, then we can write:

$$ \begin{array}{l} \dfrac{A}{B} = \dfrac{A'}{B'} = \dfrac{P.y}{P.z} = \dfrac{P'.y}{Z_{near}}\\ P'.y = \dfrac{P.y}{P.z} * Z_{near} \end{array} $$In the previous lesson, we positioned the canvas 1 unit away from the eye, making the near clipping plane equal to 1. This simplification reduced the equation to a mere division of the point's x- and y-coordinates by its z-coordinate (in other words, we ignored \(Z_{near}\)). We will also test whether the point is visible in the function that computes the projected point coordinates. We will compare the projected point coordinates with the canvas coordinates. In the program, if any of the triangle's vertices are outside the canvas boundaries, we will draw the triangle in red (a red triangle in the image indicates that at least one of its vertices lies outside the canvas). Here is an updated version of the function for projecting points onto the canvas and computing the raster coordinates of a 3D point:

bool computePixelCoordinates(

const Vec3f &pWorld,

const Matrix44f &worldToCamera,

const float &b,

const float &l,

const float &t,

const float &r,

const float &near,

const uint32_t &imageWidth,

const uint32_t &imageHeight,

Vec2i &pRaster)

{

Vec3f pCamera;

worldToCamera.multVecMatrix(pWorld, pCamera);

Vec2f pScreen;

pScreen.x = pCamera.x / -pCamera.z * near;

pScreen.y = pCamera.y / -pCamera.z * near;

Vec2f pNDC;

pNDC.x = (pScreen.x + r) / (2 * r);

pNDC.y = (pScreen.y + t) / (2 * t);

pRaster.x = static_cast<int>(pNDC.x * imageWidth);

pRaster.y = static_cast<int>((1 - pNDC.y) * imageHeight);

bool visible = true;

if (pScreen.x < l || pScreen.x > r || pScreen.y < b || pScreen.y > t)

visible = false;

return visible;

}

Here is a summary of the changes we made to the function:

-

Lines 16 and 17: The result of the perspective divide is multiplied by the near clipping plane.

-

Lines 20 and 21: To remap the point from screen space to NDC (Normalized Device Coordinates) space, we divide the point's x and y coordinates in screen space by the canvas width and height, respectively.

-

Lines 26 and 27: The point coordinates in screen space are compared with the bottom-left and top-right canvas coordinates. If the point lies outside these bounds, we set the

visiblevariable to false.

The rest of the program (which you can find in the source code section) is similar to the previous one. We loop over all the triangles of the 3D model, convert the triangle vertices' coordinates to raster coordinates, and store the results in an SVG file. Let's render a few images in Maya and with our program and check the results.

As you can see, the results match. Maya and our program produce consistent results regarding the size and position of the model in the images. When the triangles overlap the canvas boundaries, they are rendered in red, as expected.

Your explanation and code snippet are clear and informative, but there are a few areas where the text could be improved for clarity, grammar, and Markdown formatting. Here's a revised version:

When the Resolution Gate and Film Gate Ratios Don't Match

When the aspect ratio of the film gate and the resolution gate (also referred to as the device aspect ratio) differ, a decision must be made: whether to fit the resolution gate within the film gate or to fit the film gate to match the resolution gate. Below, we explore the various approaches to this situation:

In the text that follows, when we mention that the film gate matches the resolution gate, we refer solely to their relative sizes aligning. This comparison is viable despite their different units of measurement (inches for the film gate versus pixels for the resolution gate) because we are comparing their aspect ratios. For illustration, if we depict the film gate as a rectangle, we'll draw the resolution gate such that its sides either align with the top and bottom or with the left and right sides of the film gate rectangle, depending on the context (as demonstrated in Figure 8).

-

Fill Mode: This involves fitting the resolution gate within the film gate (the blue box is inside the red box). There are two scenarios to consider:

-

Figure 8a: If the film aspect ratio is greater than the device aspect ratio, we must scale down the canvas's left and right coordinates to match those of the resolution gate. This is achieved by multiplying the left and right coordinates by the device aspect ratio divided by the film aspect ratio.

-

Figure 8c: If the film aspect ratio is less than the device aspect ratio, we must scale down the canvas's top and bottom coordinates to match those of the resolution gate. This is done by multiplying the top and bottom coordinates by the film aspect ratio divided by the device aspect ratio.

-

-

Overscan Mode: This method fits the film gate within the resolution gate (the red box is inside the blue box), with two cases to handle:

-

Figure 8b: If the film aspect ratio is greater than the device aspect ratio, we need to scale up the canvas's top and bottom coordinates to align with those of the resolution gate. This requires multiplying the top and bottom coordinates by the film aspect ratio divided by the device aspect ratio.

-

Figure 8d: If the film aspect ratio is less than the device aspect ratio, we need to scale up the canvas's left and right coordinates to align with those of the resolution gate. This is achieved by multiplying the left and right coordinates by the device aspect ratio divided by the film aspect ratio.

-

Here is how these four cases can be implemented in code:

float xscale = 1;

float yscale = 1;

switch (fitFilm) {

default:

case kFill:

if (filmAspectRatio > deviceAspectRatio) {

// Case 8a

xscale = deviceAspectRatio / filmAspectRatio;

} else {

// Case 8c

yscale = filmAspectRatio / deviceAspectRatio;

}

break;

case kOverscan:

if (filmAspectRatio > deviceAspectRatio) {

// Case 8b

yscale = filmAspectRatio / deviceAspectRatio;

} else {

// Case 8d

xscale = deviceAspectRatio / filmAspectRatio;

}

break;

}

right *= xscale;

top *= yscale;

left = -right;

bottom = -top;

Refer to the next chapter for the complete program's source code.

Conclusion

In this lesson, you've gained a comprehensive understanding of simulating a pinhole camera in CG. Through this exploration, we've also delved into projecting points onto the image plane and determining their visibility to the camera by comparing their coordinates against the canvas coordinates. The insights from this lesson lay a foundational knowledge for discussing the perspective projection matrix in our next topic, understanding the REYES algorithm—a prominent rasterization technique—and grasping how images are formed in ray tracing.