Math Operations on Points and Vectors

Reading time: 12 mins.Having delineated the principles of Cartesian coordinate systems, including the relationship between coordinates of points and vectors within these systems, we now proceed to explore some of the principal operations applied to points and vectors. These operations are fundamental in the functionality of any 3D application or rendering engine.

Vector Class in C++

To begin, we will establish the structure for our Vector class in C++:

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

// Three primary methods for vector initialization

Vec3() : x(T(0)), y(T(0)), z(T(0)) {}

Vec3(const T &xx) : x(xx), y(xx), z(xx) {}

Vec3(T xx, T yy, T zz) : x(xx), y(yy), z(zz) {}

T x, y, z;

};

Vector Length

As previously mentioned, a vector can be visualized as an arrow originating at one point and concluding at another. It not only signifies the direction from point A to B but also serves to measure the distance between the two points. This measurement is derived from the vector's length, which can be calculated using the formula below:

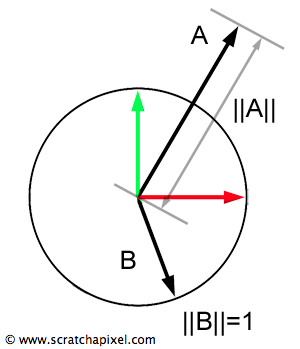

$$||V|| = \sqrt{V.x * V.x + V.y * V.y + V.z * V.z}$$In mathematical terms, the double bars (||V||) signify the vector's length. This attribute of a vector is also referred to as its norm or magnitude (figure 1).

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

...

// length can be a method from the class...

T length()

{

return sqrt(x * x + y * y + z * z);

}

...

};

// ... or you can also compute the length in a function that is not part of the class

template<typename T>

T length(const Vec3<T> &v)

{ return sqrt(v.x * v.x + v.y * v.y + v.z * v.z); }

The axes of a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system are represented by unit vectors.

Normalizing a Vector

The term "normalize" can be spelled with either an 's' or a 'z' due to varied cultural influences. However, in programming, American spelling conventions typically prevail in the naming of methods or functions, leading to the use of "normalize" with a 'z' in code.

A normalized vector, adhering to industry standards and spelled with a 'z' here, is a vector of length 1 (as illustrated by vector B in figure 1), also known as a unit vector. The process of normalizing a vector involves calculating its length and then dividing each coordinate of the vector by this length. The formula for this is expressed as:

$$ \hat{V} = \frac{V}{|| V ||}$$

The C++ implementation can be enhanced for efficiency. Specifically, vector normalization should only occur if the vector's length is greater than zero to avoid division by zero. An optimization involves calculating the inverse of the vector's length once and multiplying each vector coordinate by this inverse value, instead of dividing them by the vector's length. This approach is preferred as multiplication operations are generally less computationally expensive than divisions, which can significantly impact performance in rendering contexts where vector normalization is a frequent operation. While some compilers may automatically optimize this, explicitly coding this optimization can reduce render times.

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

...

// Vector normalization method

Vec3<T>& normalize()

{

T len = length();

if (len > 0) {

T invLen = 1 / len;

x *= invLen, y *= invLen, z *= invLen;

}

return *this;

}

...

};

// Utility function for vector normalization

template<typename T>

void normalize(Vec3<T> &v)

{

T len2 = v.x * v.x + v.y * v.y + v.z * v.z;

if (len2 > 0) {

T invLen = 1 / sqrt(len2);

v.x *= invLen, v.y *= invLen, v.z *= invLen;

}

}

The term norm in mathematics refers to a function that assigns a length, size, or distance to a vector, such as the Euclidean norm described here.

Dot Product

The dot product, or scalar product, involves two vectors, A and B, and is conceptualized as the projection of one vector onto the other, yielding a scalar value. This operation is symbolized by \(A \cdot B\) or sometimes \(\langle A, B \rangle\), involving the multiplication of corresponding elements from each vector and summing these products. For 3D vectors, the operation is:

$$A \cdot B = A.x * B.x + A.y * B.y + A.z * B.z$$This process resembles the method for calculating a vector's length, where the square root of the dot product of two identical vectors (A=B) reveals the vector's length. We can express this as:

$$||V||^2=V \cdot V$$This principle is utilized in the normalization method:

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

...

T dot(const Vec3<T> &v) const

{

return x * v.x + y * v.y + z * v.z;

}

Vec3<T>& normalize()

{

T len2 = dot(*this);

if (len2 > 0) {

T invLen = 1 / sqrt(len2);

x *= invLen, y *= invLen, z *= invLen;

}

return *this;

}

...

};

template<typename T>

T dot(const Vec3<T> &a, const Vec3<T> &b)

{

return a.x * b.x + a.y * b.y + a.z * b.z;

}

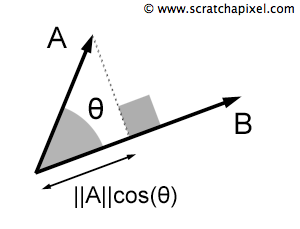

The dot product is pivotal in 3D applications for it indicates the cosine of the angle between two vectors, as illustrated in Figure 2. This operation has several applications, such as determining the angle between vectors or testing for orthogonality, where a dot product result of zero signifies perpendicular vectors.

-

If B is a unit vector, the operation \(A \cdot B\) yields \(||A||\cos(\theta)\), signifying the magnitude of A's projection in B's direction, with a negative sign if the direction is reversed. This is termed the scalar projection of A onto B.

-

For cases where neither A nor B is a unit vector, the expression can be adjusted to \(A \cdot \frac{B}{||B||}\), recognizing \(B / ||B||\) as B represented as a unit vector.

-

When both vectors are normalized, the arc cosine (\(\cos^{-1}\)) of their dot product reveals the angle \(\theta\) between them: \(\theta = \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{A \cdot B}{||A||\:||B||}\right)\) or \(\theta=\cos^{-1}(\hat{A} \cdot \hat{B})\), where \(\cos^{-1}\) denotes the inverse cosine function, commonly represented as

acos()in programming languages.

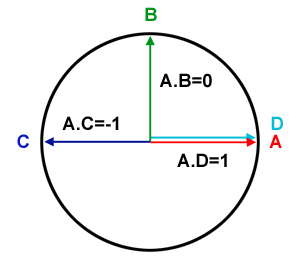

The dot product plays a crucial role in 3D geometry, serving various purposes such as testing for orthogonality. When two vectors are orthogonal (perpendicular), the dot product equals 0. If vectors point in opposing directions, the dot product is -1, and when aligned in the same direction, it equals 1. This operation is extensively used to determine the angle between two vectors or to calculate the angle between a vector and a coordinate system's axis, aiding in converting vector coordinates to spherical coordinates, as detailed in the discussion on trigonometric functions.

The Cross Product

The cross product is a vector operation distinct from the dot product, which yields a scalar value. Unlike the dot product, the cross product results in a vector. The uniqueness of this operation lies in the resultant vector being perpendicular to the plane defined by the two original vectors. The cross product is represented as:

$$C = A \times B$$

To calculate the cross product, the following formula is used:

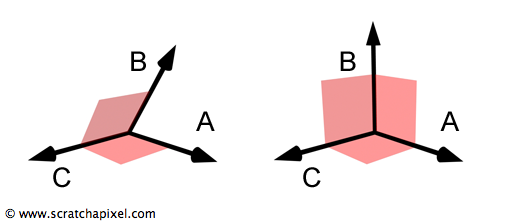

$$ \begin{array}{l} C_X = A_Y \times B_Z - A_Z \times B_Y\\ C_Y = A_Z \times B_X - A_X \times B_Z\\ C_Z = A_X \times B_Y - A_Y \times B_X \end{array} $$The cross product \(A \times B\) results in a vector, C, that is orthogonal to both A and B. These two vectors define a plane, and C stands perpendicular to this plane. The vectors A and B need not be perpendicular themselves, but when they are, and assuming they are of unit length, they form a Cartesian coordinate system with C. This concept is instrumental in constructing coordinate systems, a topic further explored in the chapter on Creating a Local Coordinate System.

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

...

// Class method for cross product

Vec3<T> cross(const Vec3<T> &v) const

{

return Vec3<T>(

y * v.z - z * v.y,

z * v.x - x * v.z,

x * v.y - y * v.x);

}

...

};

// Utility function for cross product

template<typename T>

Vec3<T> cross(const Vec3<T> &a, const Vec3<T> &b)

{

return Vec3<T>(

a.y * b.z - a.z * b.y,

a.z * b.x - a.x * b.z,

a.x * b.y - a.y * b.x);

}

A helpful mnemonic for remembering the cross product formula involves using the coordinate letters not explicitly mentioned when calculating a specific component, for instance, asking "why z?" to remember the components involved in calculating \(C_X\). More fundamentally, understanding that the cross product results in a vector perpendicular to the initial vectors allows for a logical reconstruction of this formula. The matrix representation can simplify the visualization of this operation:

$$ \begin{pmatrix} a_x\\a_y\\a_z \end{pmatrix} \times \begin{pmatrix} b_x\\b_y\\b_z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a_yb_z - a_zb_y\\ a_zb_x - a_xb_z\\ a_xb_y - a_yb_x \end{pmatrix} $$This representation shows that to calculate any component of the resultant vector (e.g., the x component), the other two components (y and z) from vectors A and B are utilized.

It's crucial to recognize that the sequence of vectors in the cross product significantly influences the outcome. For instance, \(A \times B\) yields a different result than \(B \times A\):

$$A \times B = (1,0,0) \times (0,1,0) = (0,0,1),$$while

$$B \times A = (0,1,0) \times (1,0,0) = (0,0,-1).$$

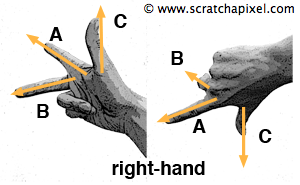

The cross product is described as anticommutative, meaning that exchanging the positions of the two vectors inverses the result: if \(A \times B = C\), then \(B \times A = -C\). This property underscores the significance of vector sequence in determining the direction of the resultant vector. When two vectors define the initial axes of a coordinate system, the direction in which the third vector—derived from their cross product—points depends on the handedness of the system, a concept previously discussed.

Even though computing a cross product between vectors yields a consistent unique outcome—for example, \(A = (1, 0, 0)\) and \(B = (0, 1, 0)\) always produce \(C = (0, 0, 1)\)—the interpretation of the resultant vector's direction is contingent on the coordinate system's handedness. This distinction is crucial because, despite the invariance of the computational result, how the resultant vector is depicted depends on whether the coordinate system is right-handed or left-handed.

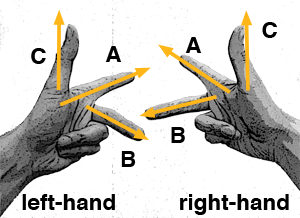

A practical mnemonic to ascertain the direction in which the resultant vector points involves using hand gestures. In a right-handed coordinate system, aligning the index finger with vector A (e.g., the tangent on a surface) and the middle finger with vector B (e.g., the bitangent when determining a normal's orientation) makes the thumb indicate the direction of vector C (e.g., the normal). Employing the left hand for the same vectors reverses the direction indicated by the thumb. It's essential to recognize that this method addresses the representation of vector direction rather than altering the computational result itself.

In the realm of mathematics, the output of a cross product is termed a pseudo vector. The sequence in which vectors participate in the cross product is critical, especially when computing surface normals from the tangent and bitangent at a point. The sequence determines whether the resulting normal points inward (inward-pointing normal) or outward (outward-pointing normal) relative to the surface. Further exploration of this topic is available in the chapter on Creating an Orientation Matrix, where the implications of vector order in cross products on surface orientation are elaborated.

Vector/Point Addition and Subtraction

In the realm of vector mathematics, operations such as addition and subtraction are quite straightforward. Multiplying a vector by a scalar or another vector results in a new vector. Vectors can be added together or subtracted from one another, among other operations. It's noteworthy that some 3D APIs make distinctions among points, normals, and vectors due to their technical differences. For instance, normals do not undergo transformation in the same manner as points and vectors do. Subtraction of two points yields a vector, while adding a vector to another vector or a point results in a point.

Despite these distinctions, practical application has shown that the effort to maintain three separate C++ classes to represent each type—normals, vectors, and points—may not justify the added complexity. Following the precedent set by OpenEXR, an industry-standard, a unified templated class named Vec3 is used to encapsulate normals, vectors, and points without differentiation in the context of coding. This approach necessitates careful management of the occasional exceptions when variables representing different types but declared under the generic Vec3 type require distinct processing methods. Below is an example of C++ code illustrating common operations, emphasizing the utility of a singular class for handling various vector-related operations:

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

...

// Overloads the addition operator for vector addition

Vec3<T> operator + (const Vec3<T> &v) const

{ return Vec3<T>(x + v.x, y + v.y, z + v.z); }

// Overloads the subtraction operator for vector subtraction

Vec3<T> operator - (const Vec3<T> &v) const

{ return Vec3<T>(x - v.x, y - v.y, z - v.z); }

// Overloads the multiplication operator for scalar multiplication

Vec3<T> operator * (const T &r) const

{ return Vec3<T>(x * r, y * r, z * r); }

...

};