Spherical Coordinates and Trigonometric Functions

Reading time: 13 mins.In addition to understanding points, vectors, normals, and matrices, mastering the concept of expressing vectors in spherical coordinates proves immensely valuable in image rendering (and CG in general). While it's possible to render images without this knowledge, incorporating spherical coordinates often simplifies complex shading challenges. This chapter also serves as a prime opportunity to revisit trigonometric functions, crucial for navigating geometric problems in computer graphics.

Trigonometric Functions

Trigonometry and the Pythagorean theorem are foundational to creating computer-generated imagery, as rendering is fundamentally a geometric endeavor. Starting with the sine and cosine functions, we'll explore how to determine angles from 2D coordinates. These functions are typically defined with respect to the unit circle, a circle with a radius of one. For a point

Where a full circle's rotation (360 degrees) equals

Trigonometric functions also stem from the relationships between the sides of a right triangle. The tangent of an angle, for example, is the ratio of the opposite side to the adjacent side of the triangle. The arctangent function, or the inverse of tangent, is particularly useful in graphics programming. While the atan function calculates the arctangent, it doesn't account for the quadrant of the angle, potentially leading to inaccuracies. The atan2 function, however, considers the signs of both atan2.

Summarizing the trigonometric functions discussed:

And their inverse functions used to find angles given a point

The atan2 function uniquely returns angles in the range

Finally, the Pythagorean theorem, essential for various calculations such as ray-sphere intersections, states:

This principle asserts that the square of the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the triangle's other two sides.

Representing Vectors with Spherical Coordinates

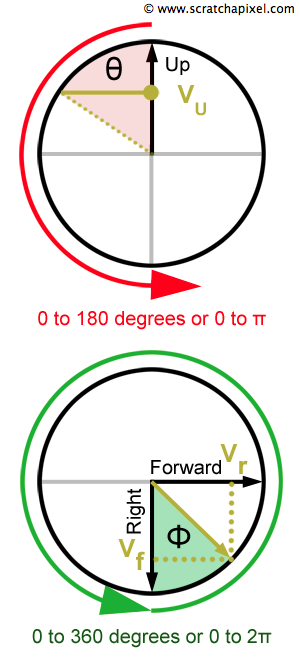

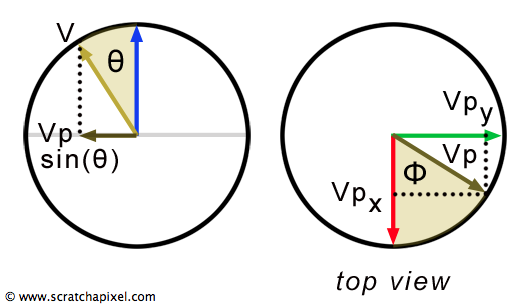

Vectors, commonly represented in Cartesian coordinates by three values corresponding to each axis, can alternatively be described using spherical coordinates, which utilize just two angles. These are the vertical angle (

Consistently within the computer graphics (CG) community,

Spherical coordinates not only simplify the representation but also play a crucial role in shading techniques, where understanding the direction relative to light sources and surfaces is key. The transition from Cartesian to spherical coordinates involves recognizing the vector in terms of its orientation within a 3D space, defined against the right (

While vectors in spherical coordinates are often normalized to unit length for simplicity, the system also accommodates vectors of any length by including a radial distance component (

The conversion process from Cartesian coordinates to spherical involves calculating the angles

Conventions Again: Z is Up!

In the realms of mathematics and physics, a conventional approach is to represent spherical coordinates within a Cartesian coordinate system where the z-axis is designated as the up vector. This differs from some computer graphics contexts where the y-axis might serve as the up vector. The standard convention, as illustrated in Figure 5, employs a left-hand coordinate system for spherical coordinates, with the z-axis as the up vector and the x- and y-axes as the right and forward vectors, respectively.

This convention is widely accepted in scholarly articles and educational resources on spherical coordinates. Although this might differ from the y-up axis convention familiar to some graphics applications, it's important to adapt to this norm for consistency in discussions and code related to spherical coordinates. The significance of this convention becomes apparent when we delve into shading, where a common technique involves transforming vectors from world space to a local coordinate system. In this local system, the surface normal at the point being shaded acts as the up vector.

In the forthcoming chapter on Creating an Orientation Matrix or Local Coordinate System, we'll explore constructing a transformation matrix that aligns with this convention. Unlike the typical approach of aligning the tangent (x-axis), normal (y-axis), and bitangent (z-axis) with the matrix's rows, we'll arrange them as follows, swapping the positions of the normal and bitangent vectors:

Here,

For a vector

Following transformation, the vector aligns with the z-axis, now representing the up vector in this local coordinate system. This adjustment might seem counterintuitive, especially when visualizing the result in a 3D application where the y-axis traditionally represents up. However, this approach effectively swaps the y- and z-coordinates, aligning the vector with the z-up convention used in mathematics and physics.

Translating Cartesian Coordinates into Spherical Coordinates

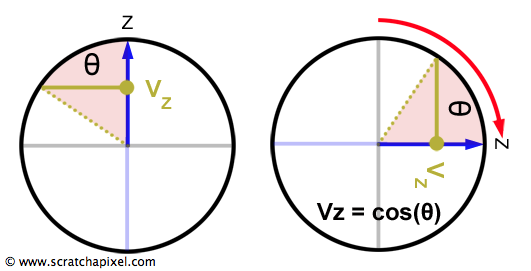

Assuming a vector is normalized simplifies its conversion to spherical coordinates. The left-hand image in Figure 6 mirrors the upper image from Figure 4, with a notable difference: the z-axis now serves as the vertical reference. Rotating this diagram by 45 degrees, as shown on the right side of Figure 6, aligns it with the scenario depicted in Figure 1, where x-coordinates were derived using

In practical terms, within a C++ environment, this translates to:

float theta = acos(Vz);

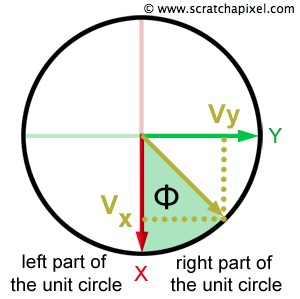

Next, we delve into determining atan2 function in C++ offers an advantage by factoring in the signs of Vy and Vx. This method yields an angle ranging between 0 to

This computation is encapsulated in C++ as:

float phi = atan2(Vy, Vx);

This methodology facilitates the translation of vectors from Cartesian to spherical coordinates, enhancing both the theoretical understanding and practical application of vectors in 3D spaces.

Converting Spherical Coordinates to Cartesian Coordinates

Transitioning from spherical to Cartesian coordinates involves a direct and elegant formula:

While memorizing this conversion might seem daunting, logical reasoning simplifies its recall. The

Here's a snippet of C++ code to perform the conversion from spherical angles to Cartesian coordinates:

template<typename T>

Vec3<T> sphericalToCartesian(const T &theta, const T &phi) {

return Vec3<T>(cos(phi) * sin(theta), sin(phi) * sin(theta), cos(theta));

};

This straightforward approach enables the efficient computation of Cartesian coordinates from spherical ones, enhancing the flexibility and utility of geometric transformations in computational applications.

Enhanced Techniques with Trigonometric Functions

Following the explanation of converting between Cartesian and spherical coordinates and their inverse process, we introduce a few practical functions. These functions are invaluable in rendering applications for manipulating vectors across both coordinate systems.

Calculating

In our discussions, we adopt a left-hand coordinate system where the z-axis signifies the vertical direction for spherical coordinates. As previously discussed, the calculation of

template<typename T>

inline T sphericalTheta(const Vec3<T> &v) {

return acos(clamp<T>(v[2], -1, 1));

}

It's essential to ensure the input vector is normalized, keeping the z-coordinate within the [-1, 1] range. Employing clamping enhances the robustness of this function.

Deriving

The computation of atan function spans the range

template<typename T>

inline T sphericalPhi(const Vec3<T> &v) {

T p = atan2(v[1], v[0]);

return (p < 0) ? p + 2 * M_PI : p;

}

Simplifying Calculations for Trigonometric Ratios

Beyond calculating angular values, obtaining direct trigonometric ratios such as

template<typename T> inline T cosTheta(const Vec3<T> &w) { return w[2]; }

However, determining

To facilitate this calculation, we introduce two functions: one for

Projecting Vectors onto the XY Plane

The computation of

The length of the projected vector

template<typename T>

inline T cosPhi(const Vec3<T> &w) {

T sintheta = sinTheta(w);

if (sintheta == 0) return 1;

return clamp<T>(w[0] / sintheta, -1, 1);

}

template<typename T>

inline T sinPhi(const Vec3<T> &w) {

T sintheta = sinTheta(w);

if (sintheta == 0) return 0;

return clamp<T>(w[1] / sintheta, -1, 1);

}

This advanced approach to vector manipulation using trigonometric functions and projections enriches the toolbox for rendering, allowing for sophisticated control over vector orientations and interactions within a 3D environment.