An Intuitive Introduction to Global Illumination and Path Tracing

Reading time: 34 mins.This content is being reviewed (Oct. 2024).

This lesson will use Monte Carlo methods to simulate global illumination. If you are unfamiliar with Monte Carlo methods, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to fully understand this lesson. If that's the case, we have covered this topic extensively in the section "The Mathematics of Computer Graphics," notably:

-

The lesson The Mathematics of Shading might also be helpful.

It is highly recommended that you read these lessons first before proceeding.

Preamble

This lesson aims to provide a lightweight introduction to the concept of path tracing, which describes a generic approach to solving the various ways in which light interacts with objects made from different materials, such as glass, concrete, or skin. Rather than diving directly into path tracing and the underlying mathematics and research papers that led to its development—topics that would require several lessons to cover—we will, for now, focus on a simple and intuitive implementation of the type of illumination problem that path tracing addresses, known as indirect diffuse lighting. This refers to the reflection of light rays by purely diffuse surfaces.

In summary, this lesson will introduce you to some fundamental concepts that will require further study to fully understand, but with a reasonably short and practical implementation of the indirect illumination phenomenon. This should not only provide you with an initial grasp of the problem but also help build your confidence and motivation. It is much easier to approach the next, more challenging lessons with a solid practical foundation than to dive straight into complex mathematical concepts, which can feel overwhelming and discouraging. That's why this lesson is placed here in the sequence: to give you the opportunity to engage with the concepts in a more accessible way before encountering the more abstract material.

What is Global Illumination, Anyway?

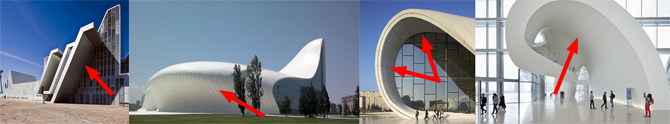

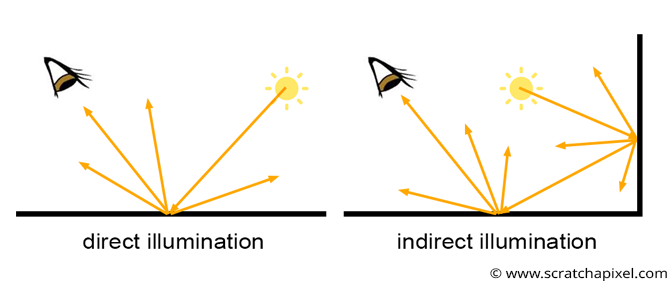

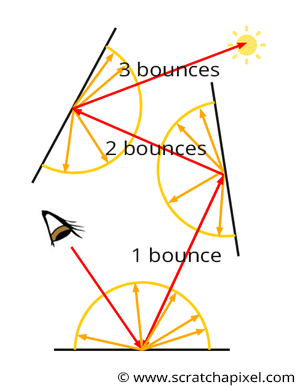

What is global illumination? As you know, we see things because light emitted by light sources, such as the sun, bounces off objects' surfaces. When light rays reflect only once from the surface of an object to reach the eye, we speak of direct illumination. But when a light source emits light rays, they often bounce off the surfaces of objects multiple times before reaching the eye (of course, this depends on the scene's configuration). To differentiate this case from direct illumination, we then speak of indirect illumination: light rays follow complex paths, bouncing from object to object before entering our eyes. This effect is visible in the images below.

Some surfaces are not exposed directly to light sources (often the sun), yet they are not entirely black. This is because they still receive light as it bounces around from surface to surface.

It is hard to quantify how much indirect illumination contributes to the brightness of a scene. As mentioned before, this depends on the scene's configuration and can thus vary greatly. Still, more often than not, indirect illumination accounts for an essential part of a scene's overall illumination. Simulating this effect is, therefore, of paramount importance if our goal is to produce images close to what we see in the real world.

Being able to simulate global illumination is a feature that every rendering system should have, so why make a big deal about it? Because while it is simple in some cases, it is complex to solve in general and also computationally expensive. This explains why, for example, most real-time rendering systems don't offer to simulate (at least as accurately as possible) global illumination effects. In short, global illumination is simple to simulate in theory (the mathematics provide the theoretical tools needed, and they are not inherently difficult). But in practice, simulating this effect efficiently, even with a super-fast computer, is a hard problem due to the computationally heavy nature of the algorithms that simulate the process itself.

Here are some reasons why this is inherently difficult:

-

It is hard to devise a generic solution that solves all light paths: light rays can interact with many different materials before reaching your eye. For example, a light ray emitted from a light source may be reflected by a diffuse surface first, then travel through a glass of water (where it gets refracted, meaning its direction changes slightly), then hit a metal surface, then another diffuse surface, and finally reach the eye. There is an infinite number of possible combinations. The path a light ray follows from the light source to the eye is called a light path. In the real world, light travels from light sources to the eye. From a mathematical point of view, we know the rules that define how light rays are reflected off the surfaces of various materials. For example, we know about the laws of reflection and refraction. Simulating the path of a light ray as it interacts with different materials is something that we can easily do with a computer. However, the problem is that forward tracing in computer graphics is not an efficient way of producing an image. Simulating the path of light rays from the light source to the eye is inefficient (see the lesson Introduction to Ray Tracing: a Simple Method for Creating 3D Images if you need a refresher on the subject). We prefer backward tracing, which involves tracing the path of light rays from the eye back to the light source where they originated. The problem is that while backward tracing is an efficient way of computing direct illumination, it is not always efficient for simulating indirect lighting. We will show why in this lesson.

-

Direct lighting mainly involves casting shadow rays from the shaded point to the various light sources in the scene. How fast we can compute direct lighting depends on the number of light sources in the scene. However, computing indirect lighting is generally much slower than computing direct lighting because it requires simulating the paths of many additional light rays bouncing around the scene. Generally, simulating these light paths is done using rays, but ray tracing, as we know, is quite expensive. As we progress through this lesson, the reasons why simulating global illumination is expensive will become clearer. For now, it is enough to say that simulating indirect illumination effects requires orders of magnitude more rays than when only direct illumination is considered. Since using ray tracing for direct illumination is already slow due to the computationally heavy nature of the ray-triangle intersection method, you can see that casting orders of magnitude more rays into the scene will only amplify that problem linearly.

Recall from this part of the lesson that there are two ways an object can receive light: directly from a light source or indirectly from other objects. Objects can also act as light sources—not because they emit light themselves, but because they reflect light from a light source or from other objects that themselves receive light from a light source or other objects, and so on. Therefore, we need to consider these objects when calculating the amount of light a shaded point receives. (Of course, for an object to reflect light, it must first be illuminated, either directly or indirectly.)

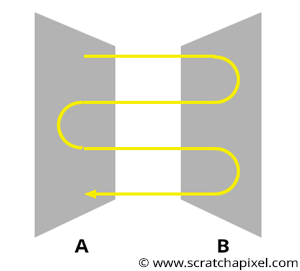

This is a complex problem because light reflected by object A toward object B might then be reflected by B back to A, which in turn reflects some of that light back to B, and so forth. The lighting of B depends on A, but the lighting of A also depends on B (see Figure 3). This process involves an exchange of energy between surfaces, which could theoretically continue indefinitely. While it is possible to express this in mathematical terms, simulating the effect on a computer is not so much complicated as it is slow and may require compromises in how accurately things are represented compared to the real world.

Simulating indirect illumination involves tracing the paths that light rays take from the moment they are emitted by a light source to when they reach the viewer's eyes. For this reason, we often refer to this process as light transport, which describes how light propagates in space as it bounces from surface to surface. A light transport algorithm (backward tracing, which we will discuss later in this chapter, is one example) is an algorithm that solves this light transport problem. As we’ll explain in this lesson, simulating light transport is a complex problem, and it is challenging to devise a single algorithm that can efficiently account for all types of light paths encountered in the real world. Indeed, light rays interacting with a glass ball do not follow the same optical rules as light rays interacting with a fully diffuse surface or a semi-transparent or translucent surface, such as skin.

How Do We Simulate Indirect Lighting with Backward Tracing?

To understand the problem of simulating global illumination with backward tracing, it’s essential first to grasp how we can simulate indirect lighting. Many attempts have been made to formalize this process—putting it into a mathematical framework. (For interested and mathematically inclined readers, additional information can be found in the reference section at the end of this lesson.) However, we will begin by explaining the process in simple terms.

From previous lessons, we know that light illuminating a given point \(P\) on the surface of an object can come from all possible directions within a hemisphere oriented around the surface normal \(N\) at \(P\). Determining the source of light is straightforward when dealing with direct light sources. We simply loop over all the light sources in the scene and either consider their direction (for directional lights) or trace a line from the light source to \(P\) (for spherical or point lights).

However, accounting for indirect lighting is more complex, as every surface above \(P\) could potentially redirect light toward it. While finding the direction of light rays from direct sources is relatively simple, how do we determine this when a surface itself emits light? We no longer have a single light position from which the light direction can be calculated. Instead, with a light-emitting surface, there’s an infinite number of points to choose from to determine the light direction.

So, why choose one direction over another, considering that every point on the surface of that object could potentially reflect light towards \(P\)? And if we were to consider all points, we would have an infinite set, which is clearly impractical.

The answer to this question is both simple and challenging. In some situations, the problem can be solved analytically; there exists a closed-form solution. This means it can be resolved with an equation. Such a solution is possible when the shapes of the objects in the scene are simple (e.g., spheres, quads, rectangles), when objects do not cast shadows on each other, and when they have uniform illumination across their surfaces. As you can see, there are quite a few conditions.

For instance, it’s relatively straightforward to calculate the exchange of light energy between two rectangular patches or between a rectangle and a sphere, as long as they are not occluded by other objects and maintain a consistent color. However, as soon as we introduce a third object between the patch and the sphere, or if we start shading these objects, the simple analytical solutions break down. (For more on this topic, you can look up the radiosity method, a popular technique in the 90s before the rise of ray tracing. Today, solving this problem through ray tracing has become the standard approach.)

Thus, we must find a more robust solution to this problem—one that works regardless of the object's shape and is not dependent on visibility. Solving this problem under these constraints is quite challenging. A simple method we can use is called Monte Carlo integration. The theory behind Monte Carlo integration is explained in detail in two lessons in the section The Mathematics of Computer Graphics. But why integration? Because, essentially, what we are trying to do is "gather" all light coming from every possible direction within the hemisphere oriented around the normal at \(P\). In mathematical terms, this gathering can be expressed using an "integral" operator:

$$\text{gather light} = \int_\Omega L_i.$$Here, \(\Omega\) (the Greek capital letter omega) represents the hemisphere of directions oriented around the normal at \(P\). It defines the region of space over which the integral is performed.

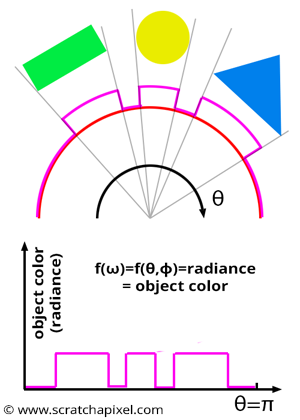

In integration, we typically work with a function. So, what is that function in our case? Figure 3 shows the illumination of \(P\) by other objects in the scene as a function. This function is non-zero wherever the objects in the scene project onto the half-disk (assuming the objects themselves are not black). This function can be parameterized in different ways: it can be a function of solid angle (represented by the Greek letter omega, \(\omega\)), or it can be expressed in terms of spherical coordinates \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) (the Greek letters theta and phi). These are just two different, but equally valid, ways of parameterizing the hemisphere. In the 2D case (Figure 3), this function can simply be defined as a function of the angle \(\theta\).

In this series of lessons on shading, we decided to avoid using technical terms from radiometry to keep the introduction approachable. However, it may be helpful at this point to introduce the concept of radiance, a term you will likely encounter if you read other documents on global illumination. Radiance is the proper term to describe light reflected by objects in the scene towards \(P\), and it is often represented by the letter \(L\).

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of an integral, we recommend reading the lessons in the Mathematics and Physics of Computer Graphics section. However, you can think of the integral symbol here as meaning, “collect the value that appears to the right of the integral sign (in this case, \(L_i\)) over the region of space \(\Omega\)." In this case, \(\Omega\) represents the hemisphere oriented around \(N\), the normal at the shaded point \(P\) (or the half-disk in the 2D case). Imagine, for example, that "grains of rice" are spread across the surface of that hemisphere. The integral means "collect or count the number of grains spread over the surface of the hemisphere." Note, however, that "grains of rice" are discrete elements, so counting them is simple. In our case, we want to measure the amount of light reflected from the surfaces directly visible from \(P\), which is more complex because these surfaces are continuous and cannot be broken down into discrete elements like grains. Yet the principle remains the same.

To understand how we approach the question of "which point on the surface of an object should we choose to compute the contribution of that object to the illumination of my shaded point \(P\)," consider this: since we use an integral to gather light from all directions, it's not a single point on the object's surface that we need, but rather all the "points" that make up its surface. However, covering an object’s surface with points is neither practical nor feasible. Why? Because points are singularities—they have no area. Thus, we can't represent a surface with an infinite number of points that have no physical size.

To solve this, one possible approach is to divide the object's surface into a large number of tiny patches and compute how much each patch contributes to the illumination of \(P\). In computer graphics, this approach is technically possible and is called the radiosity method. There is a method to solve the problem of light transfer between small patches and \(P\), though radiosity has limitations—it works well for diffuse surfaces but not for glossy or specular ones. More details on the radiosity method can be found in the following sections.

Another approach would be to divide the surfaces of objects into small patches and simulate their contributions to the illumination of \(P\) by treating these patches as small point light sources. This approach is theoretically possible, and an advanced rendering technique called VPL (Virtual Point Lights) is based on this principle. However, Monte Carlo ray tracing is ultimately simpler and more versatile.

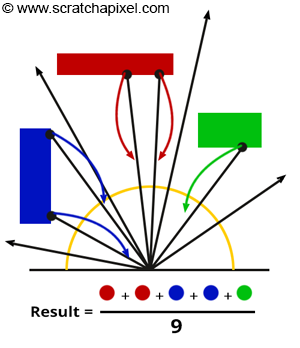

Monte Carlo is another way to address this problem. It is essentially a statistical method based on the idea that you can approximate or estimate the amount of light redirected toward \(P\) by other objects in the scene by casting rays from \(P\) in random directions above the surface and evaluating the color of the objects these rays intersect (if they do intersect any geometry). The contribution of each ray is summed, and the resulting total is divided by the number of rays. In pseudo-mathematical terms, this is expressed as:

$$\text{Gather Light} \approx \dfrac{1}{N} \sum_{n=0}^N \text{ castRay(P, randomDirectionAboveP) }.$$If you are already familiar with Monte Carlo integration, you probably already know that the equation to approximate an integral using Monte Carlo integration can be written as:

$$\langle F^N \rangle = \dfrac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} \dfrac{f(X_i)}{pdf(X_i)}.$$If you are not familiar with Monte Carlo methods, you can find an explanation in two lessons from the section Mathematics of Computer Graphics. In the equation above, you'll notice a PDF term, which we will ignore for now, just for simplicity (for your reference, PDF stands for "probability density function"). At this point, we only want you to understand the principle of Monte Carlo integration, so don’t worry too much about the technical details—we’ll cover those in the next chapter.

The easiest way to understand the Monte Carlo integration method, if you haven’t encountered it before, is to think of it in terms of polling. Suppose you want to know the average height of the entire adult population of a country. You could measure each person's height, sum up all the measurements, and divide this total by the number of people. However, there are too many people in the population, and this approach would take too long to complete. We say the problem is intractable. Instead, you might measure the height of a small sample of that population, sum up these heights, and divide the sum by the sample size (let’s call this number \(N\)).

This technique works if the people in the sample are chosen randomly and with equal probability (i.e., each individual in the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample). This is what we call a poll. The result is probably not the exact average height but is generally a "good" estimation. By increasing \(N\), you increase (in probabilistic terms) the accuracy of your estimation.

The principle is similar when approximating or estimating the amount of light reflected toward \(P\) by other objects in the scene. This problem is also intractable because we can’t account for all directions in the hemisphere (as mentioned earlier, surfaces are continuous and thus have an infinite number of points and directions, making the problem intractable). Therefore, we select a few directions randomly and take the average of their contributions.

In pseudo-code, this translates to:

int N = 16; // number of random directions

Vec3f indirectLightingApprox = 0;

for (int n = 0; n < N; ++n) {

// cast a ray above P in a random direction in the hemisphere oriented around N, the surface normal at P

indirectLightingApprox += castRay(P, randomDirectionAboveP); // accumulate results

}

// divide by the total number of directions taken

indirectLightingApprox /= N;

In computer graphics, we refer to these random directions as samples. In Monte Carlo sampling, we take samples over the domain of the integral, or the region of space over which the integral \(\int_\Omega L_i\) is performed—in this case, the hemisphere.

Don’t worry about how to choose these random directions over the hemisphere or how many samples (N) to use. We will explain this further soon. For now, remember that the Monte Carlo integration method provides only an estimation (or approximation) of the real solution, which is the result of the integral \(\int_\Omega L_i\). The "quality" of this approximation mostly depends on \(N\), the number of samples used. The higher \(N\), the more likely you are to obtain a result close to the actual integral. We will revisit this topic in the next chapter.

What do we mean by sampling? Since light can come from any direction above \(P\), in Monte Carlo integration, we instead select a few random directions within the hemisphere oriented around \(P\) and trace rays in these directions into the scene. If these rays intersect any geometry in the scene, we compute the color of the intersected object at that point. This color represents the amount of light that the intersected object reflects toward \(P\) along the direction defined by the ray:

Vec3f indirectLight = 0;

int someNumberOfRays = 32;

for (int i = 0; i < someNumberOfRays; ++i) {

Vec3f randomDirection = getRandomDirectionHemisphere(N);

indirectLight += castRay(P, randomDirection);

}

indirectLight /= someNumberOfRays;

Remember that our goal is to gather all light reflected toward \(P\) by objects in the scene, which we can express with the integral \(\int_\Omega L_i\). Here, \(\Omega\) represents the hemisphere of directions oriented around the normal at \(P\). This is the equation we aim to solve, and to approximate this integral using Monte Carlo integration, we need to "sample" the function on the right side of the integral sign (the \(\int\) symbol), specifically the \(L_i\) term.

Sampling means selecting random directions from the domain of the integral we are trying to solve and evaluating the function on the right side of the integral sign at these random directions. For indirect lighting, the domain of the integral, or the region of space over which the integral is performed, is the hemisphere of directions \(\Omega\).

Let's now see how this works with an example. For simplicity, we will start with a 2D example, but later in the lesson, we will provide code to apply this technique in 3D.

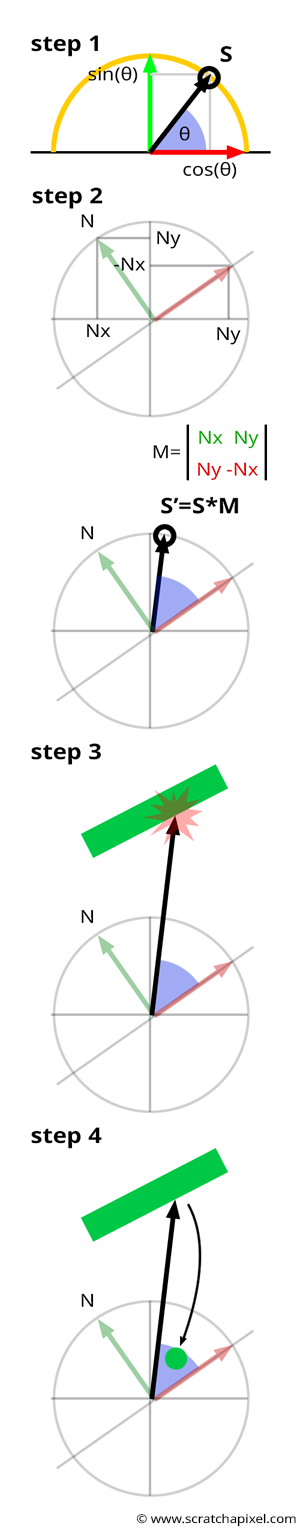

Imagine that we want to compute the amount of light arriving indirectly at \(P\). We first draw an ideal half-disk above \(P\), aligned along the surface normal at the shaded point. This half-disk serves as a visual representation of the set of directions over which we need to collect light reflected toward \(P\) from surfaces in the scene. Next, we compute \(N\) random directions, which you can think of as \(N\) points located along the outer edge of the half-disk, with their positions randomly chosen. In 2D, this can be done using the following code:

-

Step 1: First, we select a random location in the half-disk of the unit circle by drawing a random value for the angle \(\theta\) anywhere within the range \([0, \pi]\). Computing a random angle can be done with a C++ random function (such as

drand48()), which returns a random float in the range \([0,1]\). This value then needs to be mapped to the range \([0, \pi]\). -

Step 2: The "sampled" direction lies on a half-disk that is not yet aligned with the shaded point’s normal. The best way to orient it is by constructing a 2x2 matrix using the shaded point’s normal, leveraging an interesting property of 2D vectors: a 2D Cartesian coordinate system can be created from \((V_x, V_y)\) and \((V_y, -V_x)\). These vectors define the up and right axes of a Cartesian coordinate system, always perpendicular to each other. With this matrix in place, we can rotate our sample directions.

-

Step 3: Next, we trace a ray in the sampled direction. This step checks if the sampled ray intersects an object in the scene. If it does, we compute the color at the point of intersection, which we assume represents the amount of light the intersected object reflects toward \(P\) along the ray direction.

-

Step 4: Now that we know how much light is reflected toward \(P\) by an object in the scene along the sample direction, we treat the result of this intersection as a light source. In this example, we assume that the object at \(P\) is diffuse, so we multiply the object’s color at the ray intersection point by the cosine of the angle between the surface normal \(N\) and the light direction, which, in this case, is the sample direction. This follows the Lambert-Cosine Law, which states that the intensity of diffuse reflection is proportional to the cosine of the angle between the light direction and the surface normal. We also assume that all other objects in the scene are diffuse (since we call the

castRay()function recursively, which in this example computes only diffuse surface appearances). -

Step 5: Accumulate the contribution of each sample.

-

Step 6: According to the Monte Carlo integration formula, we divide the sum of the samples’ contributions by the sample size \(N\).

-

Step 7: Finally, we accumulate the diffuse color of the object at \(P\) from both direct and indirect illumination and multiply this sum by the object’s albedo (remember to divide the diffuse albedo by \(\pi\) as a normalizing factor, as explained in the shading introduction).

vec3f castRay(Vec2f P, Vec2f N, uint32_t depth) {

if (depth > scene->options.maxDepth) return 0;

Vec2f N = ..., P = ...; // normal and position of the shaded point

Vec3f directLightContrib = 0, indirectLightContrib = 0;

// compute direct illumination

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < scene->nlights; ++i) {

Vec2f L = scene->lights[i].getLightDirection(P);

Vec3f L_i = scene->lights[i]->intensity * scene->lights[i]->color;

// assume the surface at P is diffuse

directLightContrib += shadowRay(P, -L) * std::max(0.f, N.dotProduct(L)) * L_i;

}

// compute indirect illumination

float rotMat[2][2] = {{N.y, -N.x}, {N.x, N.y}}; // compute a rotation matrix

uint32_t N = 16;

for (uint32_t n = 0; n < N; ++n) {

// step 1: draw a random sample in the half-disk

float theta = drand48() * M_PI;

float cosTheta = cos(theta);

float sinTheta = sin(theta);

// step 2: rotate the sample direction

float sx = cosTheta * rotMat[0][0] + sinTheta * rotMat[0][1];

float sy = cosTheta * rotMat[1][0] + sinTheta * rotMat[1][1];

// step 3: cast the ray into the scene

Vec3f sampleColor = castRay(P, Vec2f(sx, sy), depth + 1); // trace a ray from P in random direction

// Steps 4 and 5: treat the returned color as if it was light (assume shaded surface is diffuse)

indirectLightContrib += sampleColor * cosTheta; // diffuse shading = L_i * cos(N.L)

}

// step 6: divide the result of indirectLightContrib by the number of samples N (Monte Carlo integration)

indirectLightContrib /= N;

// final result is diffuse from direct and indirect lighting multiplied by the object color at P

return (indirectLightContrib + directLightContrib) * objectAlbedo / M_PI;

}

If you are an expert in Monte Carlo methods, you may have noticed that we skipped dividing the sample contribution by the PDF of the random variable. We did this intentionally to avoid confusing readers who may not be familiar with the concept of PDF. For a complete implementation, refer to the next chapter.

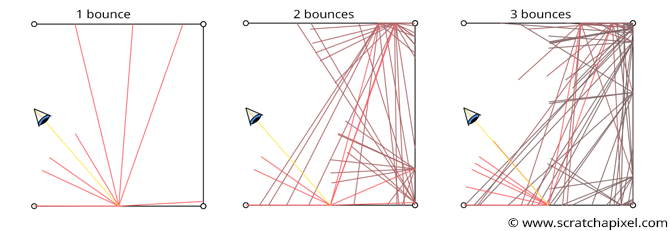

Et voilà! You’re done. You might now see why this technique is computationally expensive. To compute indirect illumination (indirect diffuse in this case, as we simulate how diffuse surfaces illuminate each other), you need to cast multiple rays (16 in the example above). Every time one of these rays intersects a diffuse surface, the same process is repeated: this process is recursive. After 3 bounces, this results in casting 16 * 16 * 16 = 4096 rays into the scene (assuming all rays intersect geometry). The number of rays increases exponentially with each bounce. For this reason, similar to mirror reflections, we stop casting rays after a specified number of bounces (for example, 3), which in the code above is controlled by the maxDepth variable.

Note that with each additional bounce, the contribution of the light is reduced. This is because each time a new ray is cast from a surface, its contribution is diminished by the cosine law. For example, with 2 bounces, a ray cast into the scene may intersect an object at point \(P_1\) (bounce 1). The color at this intersection point \(C_1\) is reduced by the dot product of the shading normal and the ray direction \(D_1\). Another ray is then cast from \(P_1\) and intersects an object at point \(P_2\), where the contribution of this ray \(R_2\) is further reduced by the cosine of the angle between the shading normal at \(P_2\) and the ray direction \(R_2\). This second ray’s contribution is also diminished by the cosine of the angle between the shading normal at \(P_1\) and the first sample direction \(D_1\). Thus, the contribution of the second bounce is attenuated twice, and a third bounce would be attenuated three times, and so on. At a certain point, simulating additional bounces has little effect on the final image (for diffuse surfaces, this usually occurs after 4 or 5 bounces, though it depends on the scene’s configuration).

Technically, you now know how to simulate indirect and direct lighting, enabling the creation of realistic images. However, the challenge is more complex than it appears. In this example, we’ve only discussed simulating indirect lighting with diffuse surfaces. Perfectly diffuse surfaces are rare in nature, and most scenes contain a combination of diffuse and specular materials. Furthermore, we haven’t yet addressed other types of materials, such as translucent ones, which don’t behave as true diffuse materials. You may wonder, "Why not use Monte Carlo integration to simulate all types of materials?" While it does work, the method becomes inefficient when the scene contains a mixture of specular, transparent, and diffuse surfaces. Let's explore some examples to understand this better.

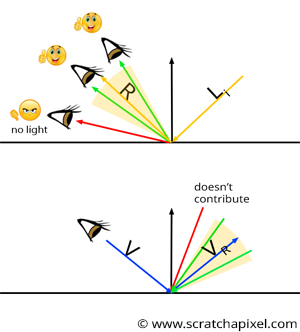

Using the Indirect Diffuse Sampling Method to Compute Indirect Specular Is Inefficient

There are essentially two kinds of material: specular and diffuse. As explained in the previous lesson, all light sources (direct or indirect) above a point on the surface of a diffuse object contribute to that point's brightness. The contribution of each light source (again, whether direct or indirect) is attenuated by the cosine of the angle between the light direction and the surface normal, but we will ignore this detail for now. Remember that diffuse reflection is view-independent. A diffuse surface will always have the same brightness, regardless of the viewing angle. Specular surfaces are different: they are view-dependent. You can only see the reflection of an object if the viewing angle is roughly aligned with the mirror reflection along which light from the object is reflected. This means that light rays reflected by a glossy surface are reflected within a cone of directions oriented around the reflection direction, as explained in the previous chapter. When computing the contribution of an object to the illumination of a diffuse object, we speak of indirect diffuse. Similarly, when computing the contribution of an object to the illumination of a glossy object, we speak of indirect specular. Remember two other things:

-

For a glossy surface, a beam of light with a given incident direction is reflected within a cone of directions (the specular lobe). The cone’s width depends on the surface roughness; the rougher the surface, the larger the cone.

-

Reflection by surfaces is a reciprocal process: If we swap the view and the incident direction, the way the surface reflects light remains the same

For a diffuse surface, any light source above it contributes to the illumination at \(P\). For a specular surface, however, a light source can only be visible if the view direction \(V\) is roughly aligned with the mirror direction \(R\) of the incident light direction. How closely \(V\) and \(R\) must align depends on the surface roughness. If the surface is very rough, light may still be reflected toward the view direction even if \(V\) is not closely aligned with the mirror direction \(R\), as shown in Figure 7 (top). However, as soon as \(V\) is completely outside the cone of directions in which the specular surface reflects light rays, no light should be reflected at all (Figure 7 - top). We can use this observation to compute the glossy reflection of an object on a glossy surface. If we know the view direction \(V\), then only light rays with specific incident directions will be reflected toward the eye along \(V\). Now imagine computing the mirror direction of the vector \(V\), as shown in Figure 7 (bottom). This gives us the vector \(R_V\). Next, imagine a cone of directions in which light rays are reflected, centered around \(R_V\). What does this tell us? Any light ray with an incident direction within that cone will be reflected along \(V\) to at least some extent.

This is a direct consequence of the reciprocity rule: all light reflected along \(V\) must have an incident direction within the cone of directions centered around \(R_V\).

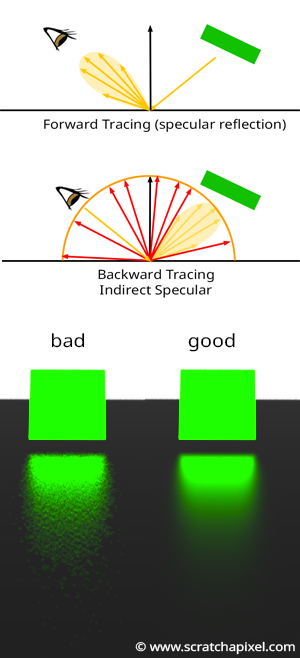

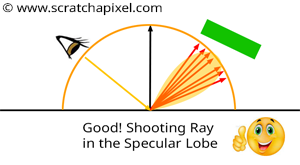

Here’s why the technique we used to compute indirect diffuse doesn’t work well for indirect specular. As explained, only light rays within the cone of directions centered around \(R_V\) contribute to the light reflected along \(V\). Thus, we should only be interested in directions within that cone (as shown in Figure 7). The problem with the technique used so far—sampling the entire hemisphere—is that many of the generated directions fall outside this cone. Another way to put it is that, because the sample directions are chosen randomly, there is no guarantee that any of the rays will be within the cone of directions for the specular lobe (Figure 8 - middle). Even if just a few rays fall within this cone, any rays outside the cone are wasted since we know that even if they hit an object, their contribution will be null. Thus, the technique is inefficient because, when we sample the hemisphere, many rays are wasted.

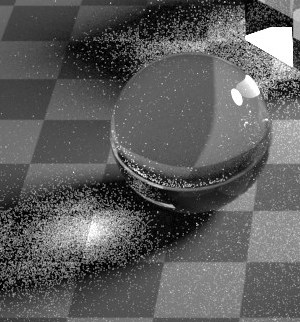

This is a simplified view of the problem. If you’re familiar with Monte Carlo integration, you’ll understand that, ideally, you want all the samples to somehow cover the function you are trying to integrate in areas where the function is not zero. Not doing this increases what we call variance, which visually appears as noise. In Figure 8, you can see the difference in the rendering of the reflection of the green square on a glossy surface. On the left, we have an example of an image with high noise, compared to the nearly noiseless image on the right. Both images were rendered with the same number of samples, \(N\). The left image has high variance, while the right one has low variance. A complete lesson in the next section will explain techniques, such as importance sampling, to reduce variance (variance reduction). You’ll also find more information on noise and how it relates to \(N\), the number of samples, and the amount of noise in the image.

Your intuition should suggest that the solution to this problem is to cast rays that all fall within the specular lobe's cone of directions (Figure 9). Their directions should still be random, as required by the Monte Carlo integration method, but should be within useful directions. There are different ways to do this, which we will study in a lesson on advanced global illumination, available in the next section.

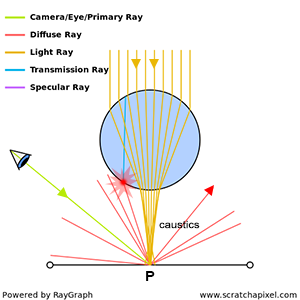

Caustics: The Nightmare of Backward Tracing

In the light transport introduction, we discussed the difficulty of simulating caustics. Caustics are created when light rays are focused at specific points or regions in space by a specular surface or due to refraction (for example, light passing through a glass of water or wine focuses at a point when it exits the glass, as shown in Figures 10 and 11).

The problem with caustics is similar to the previous issue of distributing samples over the hemisphere to simulate indirect specular reflections. As shown in Figure 11, many rays do not intersect the sphere, which concentrates light rays toward \(P\), the shaded point. One ray intersects the sphere but at a point far from where light rays converge as they exit the sphere. Even though \(P\) is likely very bright due to many light rays converging there, our Monte Carlo method fails to detect the specific sources of light illuminating \(P\). As a result, \(P\) will appear dark in the render when it should be bright. Simulating caustics creates highly noisy images, as shown in Figure 12.

Caustics differ from indirect specular reflections because, at least with indirect reflections, we have some prior knowledge of the directions in which to cast rays. These should be within the cone of directions in the specular lobe, as explained earlier. In the case of caustics, however, we don’t know where in the scene caustics are formed. We don’t know which areas of the scene will concentrate and redirect light rays toward \(P\). Of course, we could increase the sample count \(N\), but we would likely need a very large number to significantly reduce variance, which would greatly increase render time. This isn’t an efficient solution. An effective solution would reduce variance significantly while keeping render times low.

There are no reasonable ways to simulate caustics using only backward tracing, which is why researchers have developed other approaches. One common solution is to simulate light propagation through highly specular and transparent objects using forward tracing in a pre-pass. After interacting with glossy or refractive materials, light rays hit diffuse surfaces, and their contribution at these points is stored in a spatial data structure. At render time (after the pre-pass, when computing the final image), if a diffuse surface is hit by a primary ray, we consult this spatial data structure to check if energy was deposited there during the pre-pass by specular or transparent objects. This is the foundation of a technique called photon mapping, which we hope to delve into in a future lesson yet to be written.

In general, combining both backward and forward tracing to solve complex light transport provides better results than using either method alone. For example, in photon mapping, we use forward tracing in the pre-pass to track light paths as they interact with glossy and refractive objects and backward tracing for visibility and direct lighting. This approach is used in many light transport algorithms, such as photon mapping (which we’ve mentioned) and bidirectional path tracing, which we will cover in future lessons. Of course, these light transport algorithms have their limitations (too).

What’s Next?

We will study and implement indirect diffuse lighting using Monte Carlo integration in our renderer.