From the Radiative Transfer Equation to the Volume Rendering Equation

Reading time: 36 mins.In this chapter, we will learn about the equations that govern volume rendering. If you are not interested in the theory at all, then you can skip this chapter (stick to the first four chapters of this lesson that are just about practice).

How does light interact with a participating medium and propagate in volumes?

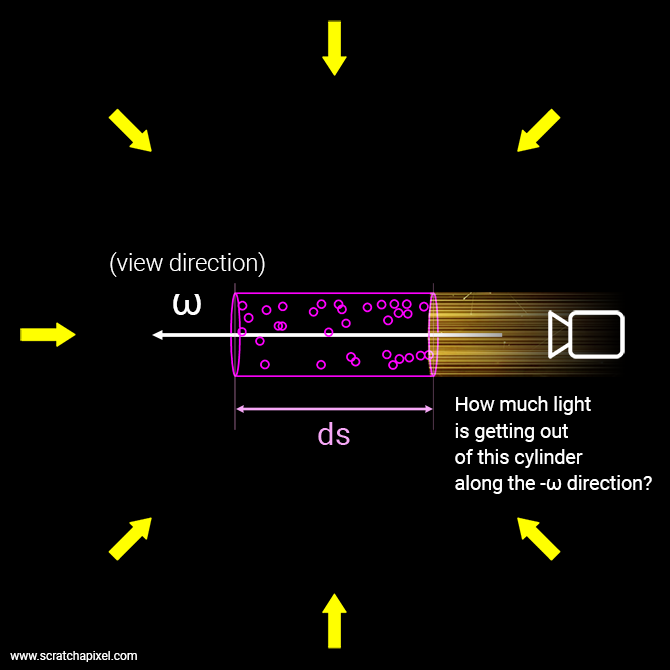

Most books and papers use the same conventions when it comes to rendering in general and rendering participating media (plural of medium) in particular. So it's a good idea to get familiarized with these conventions. Volumes are often represented as small differential cylinders. A viewer is looking down at this cylinder from one end, and we shine a collimated beam of light on the other end as depicted in the image below. What we are looking for is the intensity of that light beam (how much light reaches the viewer's eyes) after it has traveled through the volume.

-

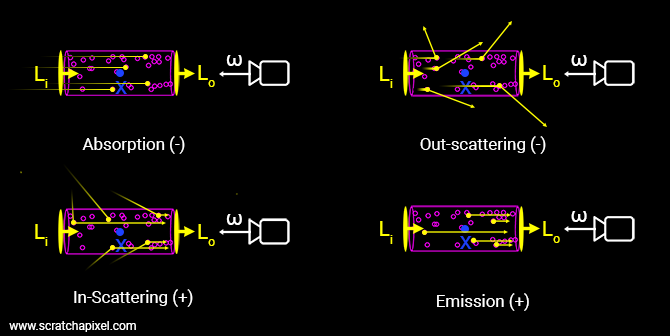

The technical term for this light quantity is radiance, which we will denote with the letter \(L\). \(L_i\) is the incoming radiance: the intensity of the light beam shone on the cylinder. \(L_o\) is the outgoing radiance: how much leaves the volume on the other end.

-

The view direction is denoted \(\omega\) (the Greek letter omega). In our code, this is the camera ray direction.

This is our basic setup. Our narrow (collimated) light beam passing through a cylinder can interact with the medium in four different ways (assuming our small cylinder is of course not empty but filled with some particles):

-

Absorption: Some of the light is absorbed. Our light beams will lose intensity. Radiance decreases.

-

Out-scattering: Photons making up our narrow beam are traveling in the direction -\(\omega\), directly towards the eye; however, they might not reach the eye because some will be scattered along the way in another (random) direction. Out-scattered photons are no longer in the beam, and thus it also loses intensity in this case. Radiance decreases.

-

In-scattering: Scattering might also cause some of the light falling upon the volume to be redirected along the path of our light beam. The beam then gains intensity. Radiance increases.

-

Emission: Gases can emit light when they reach certain temperatures. Electrons then gain energy, which is released in the form of photons. The directions taken by these photons are random, but eventually, some of them will be traveling along the path of the light beam. Thus, due to emission, the intensity of our light beam will also increase.

It is important to note that both out-scattering and absorption cause a loss in light energy, whereas in-scattering and emission cause our narrow collimated beam to gain energy as it travels toward the eye. It is also key to understand that both in-scattering and out-scattering are part of the same phenomenon: photons "colliding" with the particles making the medium.

The change in radiance \(dL\) along \(ds\) is equal to the difference between the incoming radiance \(L_i\) and the outgoing radiance \(L_o\) at point \(x\) along the direction \(\omega\). This change in radiance is also equal to the net sum of the effects of absorption, scattering (in and out), and emission:

$$dL(x,\omega) = \text{emission} + \text{in-scattering} - \text{out-scattering} - \text{absorption}$$This is not a "proper" equation, but later in this chapter, we will see how this eventually leads to what is known as the radiative transfer equation (RTE) and volume rendering equation (VRE). But before we get there, we need to learn about the absorption and scattering coefficients, Beer's law, and the phase function.

Absorption, Scattering, and Extinction/Attenuation Coefficients

It is best to introduce the absorption (and scattering coefficient) in the context of the equations in which they are used, but mixing the equations and a definition of these coefficients can be a bit confusing, so let's introduce them now.

Absorption Coefficient

The absorption coefficient (or absorption cross-section), \(\sigma_a\), expresses the probability density that light is absorbed per unit distance traveled in the medium. The unit of the absorption coefficient is a reciprocal distance (i.e., mm\(^{-1}\), cm\(^{-1}\), or m\(^{-1}\)). A probability density can be interpreted as the likelihood that a random event (e.g., an absorption event) occurs at a given point. Let's say you chose a system in which 1 unit of measurement represents 1 meter and have a volume with an absorption coefficient of 0.5. The probability that a photon is absorbed after it has traveled a distance of 1 meter through that volume would be 0.5. Shoot 1000 photons and measure how many of them will leave the volume on the other side: on average, you will get 500 photons. Said differently, half of your light intensity is lost while traveling through this volume due to absorption.

The fraction of light that is being absorbed is the same regardless of the incoming light intensity. The ratio between the number of photons entering the volume and the number of photons leaving the volume stays the same (on average) regardless of the number of photons entering the volume. The incoming radiance is independent of the absorption effect. Furthermore, there is also a linear relationship between \(\sigma_a\) and \(ds\). The absorption increases equally whether you double either the absorption coefficient or the distance traveled by the light through the volume.

Because the unit of the absorption coefficient is a reciprocal distance, the inverse of the coefficient is thus a distance. This distance is called the mean free path. You can look at it as the average distance a photon will travel through a volume before the photon and the medium interact with one another (resulting in a scattering or absorption event). The mean free path is key in simulating multiple scattering (a topic we will address in a separate lesson).

$$\text{mean free path} = \frac{1}{\sigma}$$Note that there is also a linear relationship between the mean free path and the absorption coefficient. If you double the absorption coefficient, then you halve the distance the photon will travel through the volume before interacting with the medium.

Scattering Coefficient

The scattering coefficient \(\sigma_s\) is similar to the absorption coefficient but expresses the probability that a photon is being scattered by the volume per unit distance. In- and out-scattering have different effects on the change in radiance. That is why we differentiate them. In-scattering adds light to our light beam traveling towards the eye along the \(\omega\) direction vector. Out-scattering causes a loss of energy as the light beam travels toward the eye. However, both are part of the same scattering phenomenon. The probability that a photon is being scattered in or out is thus the same and is defined by a single coefficient: the scattering coefficient expressed as \(\sigma_s\) (the Greek letter sigma).

In some documents, the scattering and absorption coefficients are defined with the Greek letter "mu": \(\mu\). This seems to be the convention in physics and in the field that studies how particles such as neutrons move through matter. In computer graphics, it's the letter sigma that seems to have been admitted as the convention.

Extinction Coefficient

As mentioned earlier, from the perspective of the effect that out-scattering and absorption have on the change in radiance, the two are indistinguishable. They both contribute to a loss in radiance as the light beam travels along the -\(\omega\) direction vector. The only thing that a viewer sees is a decrease in light intensity. Whether this attenuation of energy is the effect of photons being absorbed or scattered/reflected, it wouldn't change the viewer's experience and observation.

Of course, you could find what is due to absorption vs what's due to out-scattering by setting up a detector that would measure photons leaving in a different direction than -\(\omega\). This will become handy and meaningful when we later introduce the concept of the phase function.

This is why, when it comes to calculating the loss in radiance as light travels through the medium, we will combine the scattering and absorption coefficients into a single coefficient called the extinction or attenuation coefficient. It is expressed as:

$$\sigma_t = \sigma_a + \sigma_s$$The subscript \(t\) stands for total attenuation. You can also see it written as \(\sigma_e\).

Derivation of the Beer-Lambert Law

We introduce the Beer-Lambert law right from the first chapter of this lesson. The reason why it is a good idea to start with it is that you only need the Beer-Lambert law when you are concerned with calculating, say, a ray transmittance value (and not the radiance). Transmittance has to do with how much light goes through a particular volumetric object, which you can reformulate as "how opaque" the object is. Whereas you can see radiance as the quantity that defines how bright the volumetric object is. We will introduce the notion of transmittance more formally later.

To learn where the Beer-Lambert law comes from, we are going to start by looking at the derivative of the radiance for a light beam starting at \(x\) traveling a set $s$ along the direction \(\omega\). Technically -\(\omega\), but for brevity, we use \(\omega\) where it's understood that \(\omega\) is the direction in which the observer is looking and that the light beam is traveling in the opposite direction. You can write that derivative of radiance as:

$$dL = -\sigma_a L(x, \omega) ds.$$We mentioned earlier that both out-scattering and absorption contribute to a loss of radiance, but for simplicity, we will only assume that the loss of radiance is due to absorption to start with. We will extend and generalize the reasoning later (by introducing the scattering term).

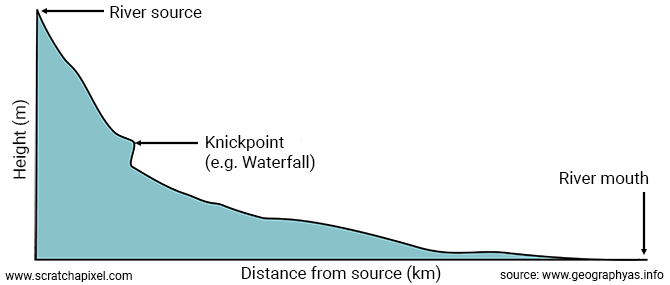

This expresses the rate at which radiance is lost due to absorption (at point \(x\) along the direction \(\omega\)). You can look at it as a measure of the slope of a riverbed at any point along the profile of that river (as depicted in the image below), or use a more technical term, the river's gradient changes as it flows from its source to its mouth.

What does this equation tell us? It tells us that the rate at which radiance changes is somehow proportional to the radiance itself at point \(x\) (so far so good) where the proportionality factor is the absorption coefficient \(\sigma_a\). Does this make sense to you? If not, try to read that sentence again until it does.

There is something important to detail here to understand what's going on. \(L(x, \omega)\) tells us what the radiance of the light beam is at point \(x\) along the direction vector \(\omega\). Because of this, people tend to overlook the fact that \(L(x, \omega)\) is a function. This function is the Beer-Lambert law itself, the function we are after. If we were to plot this function, we would see a function that decreases as the distance traveled by the light through the medium increases (as \(x\) gets further away from the point where the light beam entered the medium). The image below shows a plot of that function (for a given absorption coefficient) with respect to \(x\). The blue line represents the rate of change, the slope of the function \(L(x, \omega)\) at one particular position:

So our mission is to figure out what \(L(x, \omega)\) is using the equation \(dL = -\sigma_a L(x, \omega)\). To solve this problem, we are first going to rewrite this equation as a function of \(s\) rather than \(x\), where \(s\) represents the distance that the light beam has traveled through the medium from entry point \( x \). By substituting \(x \) with \( x_s = x + s \omega\), the equation becomes a function of \( s \):

$$\frac{dL(s)}{ds} = -\sigma_a L(s)$$The derivative here (the left-hand side of the equation) is written using the Leibniz notation form. The term in the denominator is very important. You should read the left-hand part as "the derivative of the function \(L(s)\) with respect to \(s\)." In human language, that means "at what rate does \(L(s)\) change as \(s\) changes."

To learn more about derivatives, please refer to the lesson The Mathematics of Shading.

To find \(L(s)\), you could write:

$$L(s) = \frac{dL(s)}{-\sigma_a ds}$$But that doesn't give us any more information about what \(L(s)\) is because, as you can see, \(L(s)\) appears on both sides of the equation: there is the \(L(s)\) term (the function) and the \(dL(s)\) term (the function's derivative). So how do we solve this problem?

In mathematics, this is a well-known type of equation called ordinary differential equations or ODE (first-order type here because it deals with first-order derivatives in this particular case). We won't do a lesson on what ODEs are and how to solve them now. There are plenty of documents on the Internet available that address this topic in depth. What we need to know in the context of this lesson is that it is a type of equation in which you will find both a function and its derivative. For example, the derivative of the function \(y = f(x)\) with respect to \(x\) could be written as:

$$\frac{dy}{dx} = y$$Or:

$$ y' + p(x)y = 0 \\ y' = -p(x)y $$Which is the more generic form of what is known in mathematics as a first-order homogeneous linear differential equation. Be mindful here, the term homogeneous has nothing to do with a homogeneous medium. There is another kind of first-order differential equation such as \(y' + p(x)y = q(x)\), which is said to be non-homogeneous.

The derivative and the derivative's function appear in the same equation. This is an ODE, and as you can see, the derivative \(dy\) of the function \(y\) is equal to the function \(y\) itself. Intriguing? Note that this is not the general definition of an ODE. The derivative doesn't need to be equal to the derivative's function to be an ODE. It can be any function as long as it is a function of \(x\). But in our particular case, in the case of the radiance equation, it happens that the derivative is equal to the derivative's function (and that's okay for an ODE too).

The way we solve ODEs is by moving all the \(y\)'s to one side of the equation (say the left-hand side) and everything else (most notably all the \(x\) terms but also constants, for example) to the other side. With \(c\) as a constant in our equation, we get:

$$\frac{dy}{dx} = c y \\ \frac{dy}{y} = c dx$$Remember that \(dy\) is a derivative, so to find the antiderivative's function, that is, \(y\), what we need to do next is to integrate both sides of the equation.

$$\int \frac{dy}{y} = \int c dx$$You might find it strange that we take the integral of a derivative \(dy\) "divided" by the function \(y\). Mathematically, this doesn't make any sense, so don't ever do that. The right way of looking at it is to say that you take the integral of 1 over \(y\) with respect to \(y\). We denote this as:

$$\int \frac{1}{y} dy = \int c dx$$We always take the integral of a function with respect to some variable. For example, if we want to write that we would like to take the integral of a function \(f(x)\) with respect to \(x\), we should use the following notation: \(\int f(x) dx\). The integral operator has a left symbol \(\int\) and a right symbol \(dx\). If you are still unfamiliar with derivatives, we recommend that you read the lesson The Mathematics of Shading. You will also find a lot of very good places on the Internet to learn about derivatives.

The derivative of \(\ln(y)\) is 1 over \(y\). So the integral of 1 over \(y\) with respect to \(y\) is the natural logarithm of the function \(y\), \(\ln(y)\):

$$\int \frac{1}{y} dy = \ln(y)$$You can also find plenty of references on the derivative of the \(\log()\) function, so we won't detail this part further here.

So we get:

$$\ln(y) = c \int dx$$We can move the constant \(c\) out of the integral, and the integral of \(dx\) is \(x\) itself. Therefore we now have:

$$\ln(y) = c x$$Finally, to remove the \(\ln\) on the left-hand side we can write:

$$e^{\ln(y)} = e^{cx}$$And as you know:

$$e^{\ln(y)} = y$$We arrive at the final result:

$$y = e^{cx}$$Mathematics is beautiful. What we learned here is that when we have an equation \(\frac{dy}{dx} = cy\), the solution gives us \(y = e^{cx}\). This is great for us because this equation is something we can translate into code. Let's see how this applies to our radiance equation:

$$ \begin{array}{l} \frac{dL(s)}{ds} &=& -\sigma_a L(s)\\ \frac{dL(s)}{L(s)} &=& -\sigma_a ds\\ \frac{1}{L(s)} dL(s) &=& -\sigma_a ds\\ \int \frac{1}{L(s)} dL(s) &=& \int -\sigma_a ds\\ \int \frac{1}{L(s)} dL(s) &=& -\sigma_a \int ds\\ \ln(L(s)) &=& -\sigma_a s + \color{red}{C}\\ e^{\ln(L(s))} &=& e^{-\sigma_a s}\\ L(s) &=& e^{-\sigma_a s} \end{array} $$We have omitted the constant \(\color{red}{C}\) in the calculation, but check the full derivation of the VRE equation below for a more complete solution. The general solution for a first-order homogeneous linear differential equation of the form \(y' = -p(x)y\) is:

$$ \begin{array}{l} \int \frac{1}{y} y' &=& \int -p(x) dx \\ \ln|y| &=& P(x) + C\\ |y| &=& e^{P(x)} e^{C}\\ |y| &=& \pm e^C e^{P(x)}\\ |y| &=& A e^{P(x)} \end{array} $$Where \(P(x)\) is the anti-derivative of \(p(x)\).

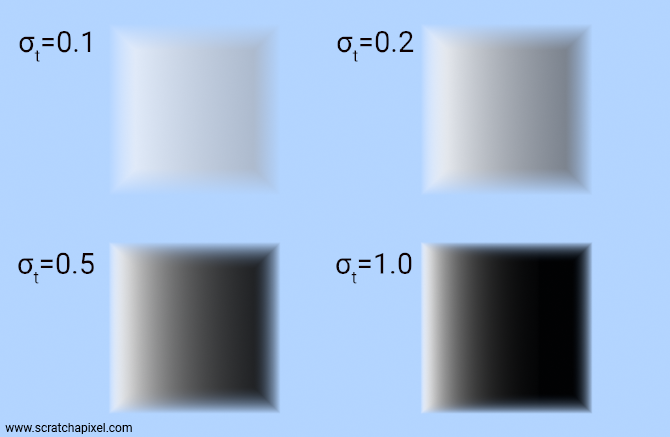

The result is the equation for the Beer-Lambert law. This equation works if the medium is homogeneous. For a heterogeneous medium, see the full transmittance equation below. Hopefully, you have been able to see that \(dL(s)\) stands for \(dy\), \(ds\) for \(dx\), \(L(s)\) for \(y\), and \(-\sigma_a\) for \(c\). As mentioned earlier, we have only considered absorption so far. But we can include the attenuation due to out-scattering in the Beer law by replacing \(\sigma_a\) with the extinction coefficient \(\sigma_t\):

$$ \begin{array}{l} L(s) = e^{-(\sigma_a + \sigma_s) s}\\ L(s) = e^{-\sigma_t s} \end{array} $$With \(\sigma_t = \sigma_a + \sigma_s\).

The image above shows the effect of the extinction coefficient on the volume's opacity and how light gets absorbed as the value of the coefficient increases.

Beer's Law, Transmittance, and Optical Depth

This leads us to the concept of transmittance. You can look at transmittance as a measure of the volume's opacity, or, say it differently, a measure of how much light can pass through a volume. More formally, transmittance is the fraction of light that is transmitted through the volume:

$$T = \frac{L_o}{L_i}$$Where, as mentioned before, \(L_i\) is the incoming radiance and \(L_o\) is the outgoing radiance. This can also be the fraction of light that passes through the volume between two points. \(T\) can be calculated using Beer's law:

$$T = e^{-\sigma_t s}$$Where \(s\) is the distance between these two points in the volume. You will often find this equation written as:

$$T = e^{-\tau}$$Where \(\tau\) (the Greek letter tau) is called the optical depth or optical thickness. You have two types of transmittance: transmittance that only accounts for absorption is called internal transmittance, whereas transmittance that accounts for absorption, out-scattering, etc., is called total transmittance.

For heterogeneous volumes, where the extinction coefficient (we will leave the concept of density aside for now) varies through space, we need to integrate the extinction coefficient along the ray, which we can write as:

$$\tau = \int_{s=0}^d \sigma_t(x_s) ds$$Where \(d\) is the distance traveled by the ray through the volume. The final and most general form of Beer's law can be written as:

$$T(d) = \exp \left(-\int_{s=0}^d \sigma_t(x_s) ds \right)$$If you read the previous chapters, you may remember that we encountered the term "tau" in the chapter Volume Rendering of a 3D Density Field. In this chapter, we used it to accumulate the extinction coefficient values as light rays pass through a heterogeneous medium.

In-scattering and the Phase Function

Finally, the last piece of the puzzle we need to put together a global equation that defines how light energy propagates through a medium is the phase function. We already introduced the concept of the phase function in the chapter Ray Marching: Getting it Right!.

When photons from the light beam interact with particles making up the medium, they can be scattered instead of absorbed. They are scattered in random directions. We know their incoming direction, but we can't predict in which direction they will be scattered. When the photons from our collimated light beam are scattered, the light beam loses energy. However, if some other light source shines on our cylinder from a direction over \(-\omega\), some of the photons from that light source traveling through the cylinder might be scattered along the \(-\omega\) direction. Because of that, the light beam traveling along the \(-\omega\) direction would gain energy. This is what we call in-scattering. The problem is that to know how much energy our light beam gains due to in-scattering, we need to know how much of the energy from the light beam passing through the cylinder at some oblique angle would be scattered in the \(-\omega\) direction. This fraction is given by what we call the phase function.

The phase function gives the fraction of incoming light traveling along the direction \(\omega'\) (note the prime sign here) that's scattered in the \(-\omega\) direction. Keep in mind that the process is three-dimensional, so light is scattered over a sphere of directions. The distribution of scattered light depends, of course, on the medium's properties and on the angle \(\theta\) (the Greek letter theta) between the light direction vector \(\omega'\) and the view direction vector \(\omega\) (these are the conventions used in the literature).

Note that you should be super careful here about the notation. When it comes to phase functions, the convention is as follows: the \(\omega\) vector points from \(x\) to the eye, and the \(\omega'\) vector points from \(x\) to the light (as shown in Figure 1). Rule of thumb: when it comes to calculating the angle between the two vectors, we will always assume that \(\omega\) points towards the eye and \(\omega'\) points towards the light. In your code, you may have to pay extra attention to this when you compute the angle theta using the light and camera direction vectors which may be pointing in the opposite direction than the expected convention.

To sum up, phase functions describe the angular distribution of light scattering at any point \(x\) within the medium.

Phase functions (denoted \(f_p(x, \omega, \omega')\)) are:

-

Reciprocal: \(f_p(x, \omega', \omega) = f_p(x, \omega, \omega')\). Swap the vectors, and the result is the same. That is the reason why phase functions are often just written down as \(f_p(x, \theta)\) where \(\theta\) is the angle between the two vectors.

-

Normalized to 1: their integration over the sphere of directions (often denoted \(\mathbb{S}^2\)) needs to be 1, otherwise, they would add or subtract radiance to a scattering event: $$\int_{\mathbb{S}^2} f_p(x, \omega, \omega') d\theta = 1.$$

A participating medium can exhibit two types of scattering behavior:

-

Isotropic: all directions in the sphere of directions are equally likely to be chosen.

-

Anisotropic: some directions in the sphere of directions are more likely to be chosen than others, preferentially in the backward or forward direction, as shown in the image below. Clouds, for example, exhibit a strong forward scattering behavior.

Here is the phase function for an isotropic medium:

$$f_p(x, \omega, \omega') = \frac{1}{4 \pi}.$$In the chapter Ray Marching: Getting it Right!, we already introduced the Henyey-Greenstein or HG phase function, one of the most commonly used anisotropic phase functions. The function only depends on the angle \(\theta\) and is defined as:

$$f_p(x, \theta) = \frac{1}{4 \pi} \frac{1 - g^2}{(1 + g^2 - 2g \cos \theta)^{\frac{3}{2}}}.$$For proof that this equation is normalized, see Ray Marching: Getting it Right!.

It was initially designed to model the scattering of light by intergalactic dust (Henyey, L.C., and J.L. Greenstein. 1941. Diffuse radiation in the galaxy. Astrophysical Journal 93, 70-83), but due to its simplicity, it has also been applied for simulating many other scattering materials. For production purposes, while simple, this function is generally good enough (furthermore, to simulate multiple scattering, the phase function needs to be inverted, and this can easily be done with this equation).

Where \(-1 \lt g \lt 1\), \(g\) is called the asymmetry parameter. When \(g\) is less than 0, light is preferentially scattered backward (backward-scattering); when \(g = 0\), the medium is isotropic (light is equally scattered in all directions); and when \(g \gt 0\), light is preferentially scattered forward (forward-scattering). In the image above, we showed an example with \(g = -0.2\) and \(g = 0.2\). The greater \(g\), the more light is being scattered back toward the light or forward towards the camera/eye. Clouds exhibit a strong forward scattering effect with values of \(g \approx 0.8\) (J. E. Hansen. 1969. Exact and Approximate Solutions for Multiple Scattering by Cloudy and Hazy Planetary Atmospheres). This causes the fringe effect at the edge of the clouds when they are backlit.

Other phase functions can be used, such as the Schlick, Mie, or Rayleigh phase functions. Check our future lesson on multiple scattering applied to participating media to learn more about these other models.

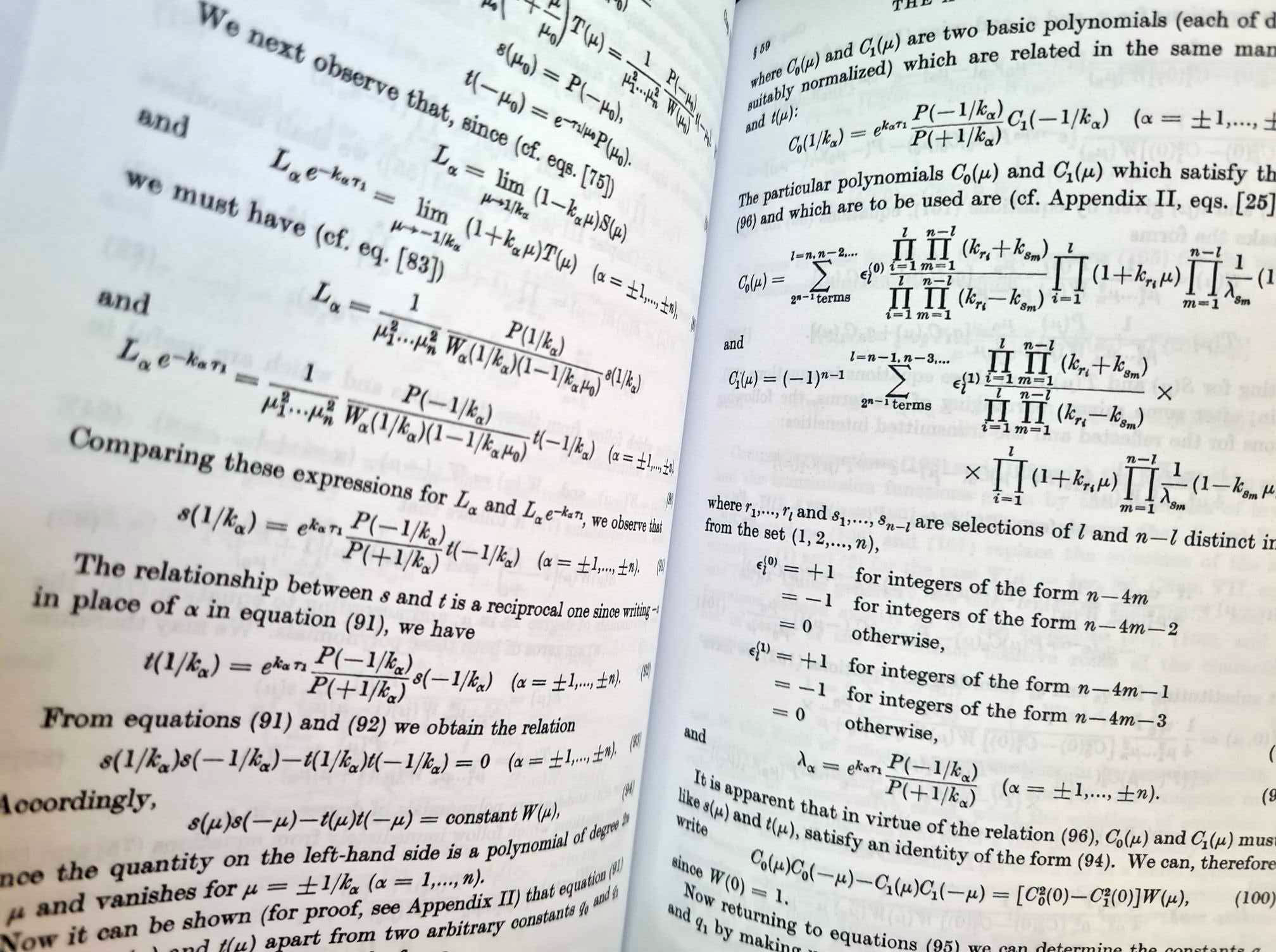

The Radiative Transfer Equation and Volume Rendering Equation

We now have all the pieces of the puzzle to put together our final equations. The first equation we will look at is called the Radiative Transfer Equation or RTE. It was defined in its modern form by a man called Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in a book entitled "Radiative Transfer," published in 1950, which has since become iconic (at least as the reference on the subject matter). Now, we won't spend too much time on that because the book itself is, well... how to put it, quite complex as you can see with this quick peek into the book.

We might eventually dive into the Radiative Transfer Equation in a future revision of this lesson or a separate lesson (if you are interested, look up the finite element methods or radiosity method and this paper "Modeling the Interaction of Light Between Diffuse Surfaces" and/or this book "Radiosity and Realistic Image Synthesis" - Cohen, 1993). For now, we will just give a small excerpt from the book, which we think is a good summary (or introduction) to everything we've learned so far:

In this chapter, we shall define the fundamental quantities which the subject of Radiative Transfer deals with and derive the basic equation— the equation of transfer— which governs the radiation field in a medium that absorbs, emits, and scatters radiations.

Ok, enough words. The RTE takes into consideration the different elements that we have listed as contributing to a change of radiance in the energy flow direction \(\omega\): absorption, in-scattering, and out-scattering, as well as emission, which we will omit in this lesson. Remember, this equation defines a change of radiance (a derivative) along the direction \(\omega\):

$$ \frac{L(x+s \omega, \omega)}{ds} = \color{blue}{-\sigma_t L(x,\omega)} + \color{orange}{\sigma_s \int_{\mathbb{S}^2} f_p(x, \omega, \omega')L(x,\omega')d\omega'} $$The scalar \(s\) refers to the positional change in direction \(\omega\) as introduced in the beginning of this chapter.

The term in blue accounts for losses due to absorption and out-scattering. The term in orange is the in-scattering term, also sometimes referred to as the source term. Note the \(\sigma_s\) term in front of the integral. This is conceptually similar to the equations we introduced earlier in the chapter for the loss of energy due to absorption and out-scattering:

$$ \begin{array}{l} dL &= -\sigma_a L(x, \omega) \\ dL &= -\sigma_s L(x, \omega) \end{array} $$The amount of in-scattering is proportional to the probability that light is being scattered. This probability is given by the scattering coefficient \(\sigma_s\). The rest of the in-scattering term was described above. The integral over the sphere of directions \(\mathbb{S}^2\) means that for the in-scattering term, we need to account for light coming from every direction (\(\omega'\)), weighted by the phase function \(f_p(x, \omega, \omega')\).

For brevity, let's write:

$$L_s(x, \omega) = \int_{\mathbb{S}^2} f_p(x, \omega, \omega')L(x, \omega')d\omega'$$We have insisted on this a lot already, but the RTE equation is an integro-differential equation. It expresses a directional derivative: the derivative of radiance \(L\) at \(x\) in direction \(\omega\). In the literature, you will also see this equation written in the following form:

$$(\omega \cdot \nabla_x)L(x, \omega) = \color{blue}{-\sigma_t L(x, \omega)} + \color{orange}{\sigma_s L_s(x, \omega)}$$Where the \(\nabla_x\) (called the Del or nabla symbol in mathematics) can be interpreted as the function's gradient (which the multidimensional concept of a derivative). We added the suscript \(x\) to denote the gradient with respect to the three coordinates of position x in 3D space. Without, \(\nabla_x\) could also compute the gradient with respect to a change in direction \(\omega\). Radiance is locally changing (either decreasing or increasing) as you move in the direction \(\omega\) at a rate that is proportional to the absorption and scattering terms. Contrary to the Volume Rendering Equation that we will introduce next, this integro-differential equation tells us at which rate radiance changes as we take "a step" in the light flow direction.

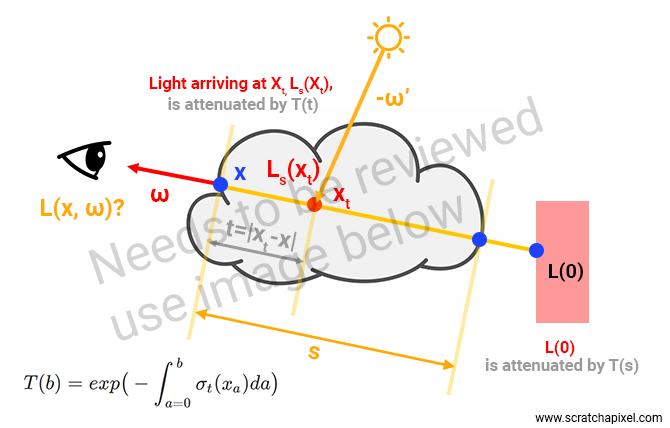

Now, this differential equation is not very useful to us because what we need as computer graphics developers is a way of measuring radiance at the boundaries of, say, a volumetric object. That radiance would be the result of light passing through the object along the ray or eye direction, reduced by either absorption and/or out-scattering, and increased by in-scattering as shown in the now-familiar figure below.

As mentioned several times already, the Radiative Transfer Equation is a first-order differential equation that, in its standard form, can be defined/written as:

$$y' + p(x)y = \color{red}{q(x)}$$In mathematics, this equation is known as a first-order non-homogeneous linear differential equation. We need to solve an equation in which both the function \(y\) and its derivative \(y'\) are present. We will redefine our radiance function now as a function of the distance \(s\), which is the distance from \(s\) to any point along the light beam with vector direction \(\omega\):

$$ \begin{array}{l} y \rightarrow L(s) \\ y'(x) \rightarrow \frac{dL(s)}{ds} \\ \end{array} $$And:

$$ \begin{array}{l} p(x) \rightarrow \sigma_t \\ q(x) \rightarrow \sigma_s L_s(s) \end{array} $$So we can write:

$$ \begin{array}{l} y' + \color{blue}{p(x)} y = \color{red}{q(x)} \\ L'(s) + \color{blue}{\sigma_t} L(s) = \color{red}{\sigma_s L_s(s)} \end{array} $$Remember that we said that the term \(L_s\) was sometimes referred to as the source term. This is because you can look at it as essentially light "showing up" in places along the ray and being added to the radiance of the beam. It is a "source" of radiance.

This standard form ODE has a known solution (see the derivation below if you are interested) which is:

$$y(x) = \int_{t=0}^x \color{red}{q(t)} e^{-\int_t^x \color{blue}{p} dt'} dt + C_1 e^{-\int_{t=0}^x \color{blue}{p} dt}$$Derivation

Several methods can be used to derive a solution to the first-order non-homogeneous differential equation. We will use the integrating factor method. It starts with the idea that we can multiply the ODE \(y' + p(x)y = q(x)\) by a function \(I(x)\). If we do so, then we get:

$$\color{red}{I(x)y' + I(x)p(x)y} = I(x)q(x)$$Let's call this equation our modified ODE. To understand why it's relevant, you need to know that the derivative of the product of two functions is equal to:

$$\frac{d}{dx} [f(x) g(x)] = f'(x) g(x) + f(x) g'(x)$$This is known in mathematics as the Product Rule. Now that we know that, we can note that if we choose \(I'(x) = I(x)p(x)\), then the left-hand side of our ODE multiplied by \(I(x)\) looks like it could be a derivative computed by the Product Rule.

$$ \begin{array}{l} \color{red}{I(x)y' + I(x)p(x)y} \\ I'(x) \rightarrow I(x)p(x) \\ \frac{d}{dx} [I(x)y] = \color{red}{I(x)y' + I'(x)y} \end{array} $$Then note that \(I'(x) = I(x)p(x)\) is a first-order homogeneous differential equation in itself, and we provided a general solution earlier in this chapter for this kind of equation. The general solution is:

$$I(x) = e^{Q(x)}$$Where \(Q(x) = \int p(x) dx\). Note that \(Q(x) = -P(x)\), and \(P'(x) = -p(x)\) (see the derivation for homogeneous ODE above for the details). Let's now rewrite our modified ODE by substituting the term \(I(x)\) with the general solution for the homogeneous ODE:

$$ \begin{array}{l} I(x) y' + I(x) p(x) y &= I(x) q(x) \\ I(x) \rightarrow e^{-P(x)} \\ \color{blue}{e^{-P(x)} y' + e^{-P(x)} p(x) y} &= e^{-P(x)} q(x) \end{array} $$Finally, we know that:

$$ \begin{array}{l} I(x) y' + I'(x) y &= \frac{d}{dx} [I(x) y] \\ I(x) &= e^{-P(x)} \\ I'(x) &= I(x) p(x) \\ \color{blue}{e^{-P(x)} y' + e^{-P(x)} p(x) y} &= \color{red}{\frac{d}{dx} [e^{-P(x)} y]} \end{array} $$Therefore, substituting the left-hand term with the right-hand term in our previous equation we get:

$$\color{red}{\frac{d}{dx} [e^{-P(x)} y]} = e^{-P(x)} q(x)$$We are left with integrating both sides:

$$ \begin{array}{l} e^{-P(x)} y &= \int e^{-P(x)} q(x) dx \\ y &= \frac{1}{e^{-P(x)}} \int e^{-P(x)} q(x) dx \\ y &= e^{P(x)} \int e^{-P(x)} q(x) dx \end{array} $$In its generic form (taking into account the constant of integration, which we have omitted in the integration above), the solution becomes:

$$y(x) = e^{-\int p(x) dx} \left( \int e^{\int p(x') dx'} q(x) dx + C \right)$$All you have to do to get to the VRE is to replace the terms \(p\) and \(q\) with \(\sigma_t\) and \(\sigma_s L_s(x)\) respectively.

If we replace the \(q\) and \(p\) terms with their counterparts from the RTE equation, we get (please read the second note below):

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} L(x, \omega) =& \int_{s'=0}^s \exp\left(-\int_{s'}^{s} \textcolor{blue}{\sigma_t(x_{s''})} \, ds''\right) \left[\textcolor{red}{\sigma_s(x_{s'}) L_s(x_{s'})}\right] ds' + \\ &L(0) \exp\left(-\int_{s'=0}^{s} \textcolor{blue}{\sigma_t(x_{s'})} ds'\right) \end{split} \end{equation} $$-

The 3D position \( x \) along the ray is reparametrized by scalars \( s' \) and \( s'' \) measuring the distance along the ray, starting from the entry point \( x \). Formally, we substitute \( x \) by \( x_s = x + s \omega \).

-

The outer integral (with variable \( s' \)) runs from the entry point \( x \) in the volume to the exit point \( x_s \) of the volume (the point where we want to get a value for the light that has been traveling to that point), so effectively over a distance of \( s \), representing the accumulation of light scattered into the ray's direction along its path.

-

The inner integral (with variable \( s'' \)) runs from the current scattering point \( x_{s'} \) to the end point \( x_s \) of the ray, effectively over a distance \( s' \), representing the attenuation of light from the scattering point \( x_{s'} \) to the end point \( x_s \).

-

The term \( L(0) \exp\left(-\int_{s'=0}^{s} \textcolor{blue}{\sigma_t(x_{s'})} ds'\right) \) accounts for the initial radiance \( L(0) \) attenuated over the entire path length \( s \).

This, as you guessed, is the Volume Rendering Equation.

If you wonder why, in expanding the terms of the equation given in the derivation (see the box above), the leading exponent term appears in the second part of the equation but disappears from the first part, it’s a very good question. This is because we can write:

$$\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx = \int_0^t \sigma_t(x) \, dx + \int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx.$$In other words, the integral from \(0\) to \(s\) can be split into the integral from \(0\) to \(t\) plus the integral from \(t\) to \(s\). Therefore:

$$ \int_0^t \sigma_t(x) \, dx = \int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx - \int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx.$$Applying the exponential to both sides, we get:

$$e^{\int_0^t \sigma_t(x) \, dx} = e^{\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx - \int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx}.$$The original integral in the exponent can be split into two integrals. The subtraction in the exponent indicates the different limits of integration. Let's apply this to our equation:

$$L(x, \omega) = e^{-\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \left( \int_0^s e^{\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx - \int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \sigma_s(t) L_s(t) \, dt + C \right).$$Which simplifies to:

$$L(x, \omega) = e^{-\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \left( e^{\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \int_0^s e^{-\int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \sigma_s(t) L_s(t) \, dt + C \right).$$The outer exponential terms \(e^{-\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx}\) and \(e^{\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx}\) cancel each other out:

$$L(x, \omega) = \int_0^s e^{-\int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \sigma_s(t) L_s(t) \, dt + C e^{-\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx}.$$Here, \(C\) is the constant that represents the initial condition \(L(0)\):

$$L(x, \omega) = \int_0^s e^{-\int_t^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx} \sigma_s(t) L_s(t) \, dt + L(0) e^{-\int_0^s \sigma_t(x) \, dx}.$$Now we have the final form of the VRE as:

$$ \begin{align*} L(x, \omega) =& \int_{s'=0}^s \exp\left(-\int_{s'}^{s} \sigma_t(x_{s''}) \, ds''\right) \left[\sigma_s(x_{s'}) L_s(x_{s'})\right] ds' + \\ & L(0) \exp\left(-\int_{s'=0}^{s} \sigma_t(x_{s'}) \, ds'\right). \end{align*} $$Note though that while we don't exactly know who was the first author to come up with this term, the term Volume Rendering Equation was introduced quite late in the early 2000s. It can be found in the document entitled Volume Rendering for Production published by Pixar Research in 2017 but had been used before. If you have some information about this, let us know.

The \(L_0\) term on the right corresponds to radiance coming from an object that is potentially behind the volume object (from the viewer's point of view). If the volume object is placed in front of a solid object, radiance \(L_0\) "reflected" by the object along the \(\omega\) vector will be attenuated by the volume's transmittance over the entire distance \(s\) as depicted in the image above.

Note also that if we were to consider emission, we would add an emission term \(L_e\) next to the in-scattering term like so (note the \(\sigma_a\) term next to the emission source):

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} L(x, \omega) =& \int_{s'=0}^s \exp\left(-\int_{s'}^{s} \textcolor{blue}{\sigma_t(x_{s''})} \, ds''\right) \left[\textcolor{red}{\sigma_s(x_{s'})} L_s(x_{s'}) + \textcolor{red}{\sigma_a(x_{s'})} L_e(x_{s'})\right] ds' + \\ & L(0) \exp\left(-\int_{s'=0}^{s} \textcolor{blue}{\sigma_t(x_{s'})} ds'\right) \end{split} \end{equation} $$The Volume Rendering Equation is more useful for us computer graphics-focused people because it turns the RTE into an integral which, even if it doesn't have a closed-form solution, can at least be solved using techniques such as the Riemann sum (what we have essentially been doing through the previous chapters).

With:

$$T(s) = \exp\left(-\int_{s'=0}^{s}\sigma_t(x_{s'}) ds'\right)$$Which, as you know now, provides the transmittance of the medium over distance \(s\), we can write the VRE as:

$$L(x, \omega) = \int_{s'=0}^s T(s')\left[\sigma_s(x_{s'}) L_s(x_{s'}, \omega)\right] ds' + T(s)L(0)$$-

The outer integral (with variable \( s' \)) runs from the entry point to the exit point \( x_{s'} = x_s \) of the volume, representing the accumulation of light scattered into the ray's direction along its path.

-

The inner integral \(T(s)\) accounts for the attenuation of light from the scattering point to the exit point.

-

\( s \) is the total distance the light travels through the volume.

In general, at this point, people say that this equation can be understood intuitively. Let's see. The idea goes like this: you can see the process for computing the radiance at point \(x_s\) as the process of collecting radiance along the ray where the radiance at any point along that ray (say \(x_{s'}\) traveling towards \(x_{s}\) in the direction \(\omega\)) is being extinguished by the transmittance from that point to \(x_{s}\) (and where \(s'\) is the distance from \(x_{s'}\) to \(x_{s}\)).

If you have been that far, congratulations. You have been through one of the most complicated equations in computer graphics literature. Note that while some older papers do provide some clues about how to get from the RTE to the VRE, Scratchapixel is the first and only source (to our knowledge) that provides the full derivation (a special thanks to SP for the pointers).

A bit of history

If there is one paper that we should mention for this introduction to volume rendering, it would be the paper published by James T. Kajiya in 1984 entitled Ray-Tracing Volume Density. This tells you that rendering volume objects certainly isn't a recent thing, but the hardware back then wasn't powerful enough to even apply ray tracing to solid surfaces and thus even less so to ray-march volume objects. It's only in the late 1990s - early 2000s with films such as Contact, that we started seeing volume rendering being used in production (because the cost just became tolerable for large-budget production films). The image below is a screenshot of his paper where Kajiya was showing the very first-ever results of ray-marched volume objects.

This paper is probably one of the top 10 most important papers in the whole computer graphics research history. If you don't agree, let us know.

The big question is now: how do we calculate this integral (and no, the answer is not 42)? We have already shown one solution in this lesson with the ray-marching method, but other methods exist. Once the norm, ray-marching is now considered rather outdated (but is still a good starting point to learn about volume rendering, we think). Today the norm is to use tracking algorithms and stochastic sampling methods. We will briefly touch on this topic in the last and final chapter of this lesson.

Going from the Equation to the Code

We understand the equations can be overwhelming and that some readers will only care about how they translate into code. The first four chapters of this lesson will take you through that journey, so we won't be going through this exercise here again. We recommend you go through the first chapters of this lesson if you haven't done so already. But here are some pointers to help you connect the different parts of the equation to the various chapters.

-

The \(L(0)T(s)\) term alludes to what we learned in the first chapter of this lesson. \(L(0)\) simply accounts for the light that is being reflected by a solid object, such as the red wall in the image below, passing through the volume. That light (the object's color) is simply attenuated by \(T(s)\), where \(s\) is the distance traveled by the light through the volume, and \(T\) is simply the Beer Law. If the object is homogeneous, this is simply \(T(s) = \exp(-s * \sigma_t)\). See chapter 1 for this part. If the volume is heterogeneous, you will need to calculate the volume optical thickness as described in chapter 3. The equation is \(T(s) = \exp(- \int_{t=0}^s \sigma_t(x_t) dt)\). If we only consider this term, the volume sphere remains black as shown in the image below. This term is only responsible for the light coming from the background and passing through the volume.

-

The first term on the right-hand side of the equation, this bit \(\int_{t=0}^s T(t)\left[\sigma_s(x_t) L_s(x_t, \omega)\right] dt\), simply accounts for the single scattering term. To see how this translates into code, please read from chapter 1 through chapter 3. This term is responsible for the sphere illumination.