What's Next? Stochastic Method for Monte Carlo

Reading time: 8 mins.What we will study next

Most of this lesson's content is devoted to studying the ray-marching algorithm but you should know that while this algorithm was used almost exclusively for volume rendering until relatively recently (the mid-2010s at least), modern rendering engines are now generally using a stochastic Monte-Carlo based approach with it comes to rendering volumes instead. So why did we spend so much time studying this algorithm if it's considered superseded? For historical reasons and because it's much easier to get introduced to the topic of volume rendering (and the Volume Rendering Equation) through the ray-marching algorithm than through stochastic methods that are significantly more complex (particularly from the point of view of someone new to CGI programming with little to no math background).

Why is the ray-marching algorithm superseded? For essentially two reasons:

1. because it poorly simulates how light behaves in the real world when it interacts with a volume. We will say more about this in a moment. Two, because the stochastic approach does a much better job of simulating the real thing.

2. We could have used the stochastic method right from the beginning then (this method is well known since the 1960s) but you see, the issue with this method is that it requires zillion times more computations than the ray-marching method and you had to wait an infinitely long time to produce an image with it (at least it felt that way). Ray-marching is computationally intensive but not as much as the stochastic method and that's why it stayed until recently the go-to solution for volume rendering (and even then we had to wait until the very late 1990s to start seeing ray-marching being used in production and until the late 2000s to start seeing it used ubiquitously). Thankfully with the continuous rise in computing power, we can now produce results with the stochastic method within reasonable times, and since it creates better results, the ray-marching method has been phased out in favor of stochastic-based approaches instead. Quod erat demonstrandum.

Let's now look at why ray-marching does a rather poor job.

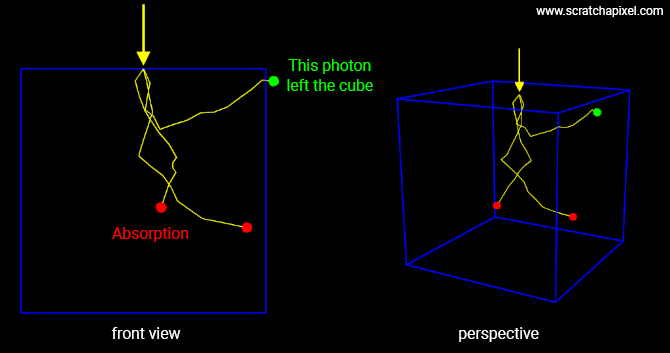

To answer this question, we need to understand how light travels through a medium. Here is what happens to a photon that enters a volume. It travels in a straight line for a certain distance until it eventually interacts with the medium (for example a particle making up the volume). As we know it can then be scattered (in which case it would change direction) or be absorbed. If it is scattered, it will then continue to travel through the volume but in a random direction, at least a direction that is very likely different from the direction it followed before interacting with the volume's particle. This "travel-interact" cycle keeps going for as long as the particle either gets absorbed or eventually leaves the volume. We have illustrated this idea in the image below, where you can see the fate of three photons entering a volume cube from the top.

Two of them (in red) get eventually absorbed, while only one of them (green) escapes the volume (in a direction that's different from the direction it followed when entering the cube).

Photons follow what can be described as a kind of random walk. And no surprise, that's actually what it is called. A random walk. We also can see that the particle interacts with the medium multiple times before either being absorbed or escaping the volume. It's scatted multiple times. And that's where the ray-marching does a poor job: it only accounts for a single interaction between the photon and the volume.

Single vs Multiple Scattering. Low vs. High Albedo Volume Objects.

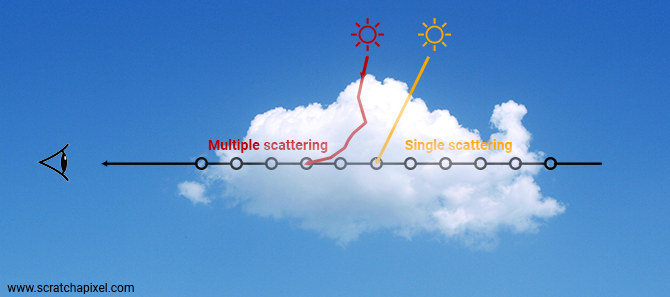

This is called single scattering. We only account for the light that's being redirected toward the viewer after a single interaction with the medium. While some volumes have a strong single scattering term (such as the dark smoke coming out of stream trains or volcanoes) many other types of volume, most notably clouds, exhibit a strong multiple scattering behavior. Photons interact with the object many many times before escaping (or being absorbed). This is what makes clouds so bright or white if you prefer, whereas the smoke coming out of steam trains or volcanoes is dark instead. We say that white clouds have a high albedo while dark smoke plumes have a low albedo. The image below shows the difference between a low and high albedo volume (the smoke on the left contains a lot of particles, whereas clouds are made out of water droplets which mostly explains the visual difference between the two). Of course, dark smoke is dark because it also absorbs a lot of light.

In summary, the ray-marching algorithm provides an acceptable approximation for low albedo objects (such as smoke) whose appearance is the result of the dominance of the single-scattering term (the orange ray depicted in the image below), whereas it provides a poor way of simulating the appearance of high albedo objects, whose appearance is the result of the dominance of multiple-scattering over single-scattering (most of the photons escaping the volume do so after interacting with the volume multiple times and not just one time as assumed with single scattering).

By the way, since we are on the topic of comparing smoke and clouds, note also that smoke is generally isotropic while clouds exhibit a strong (forward) scattering behavior.

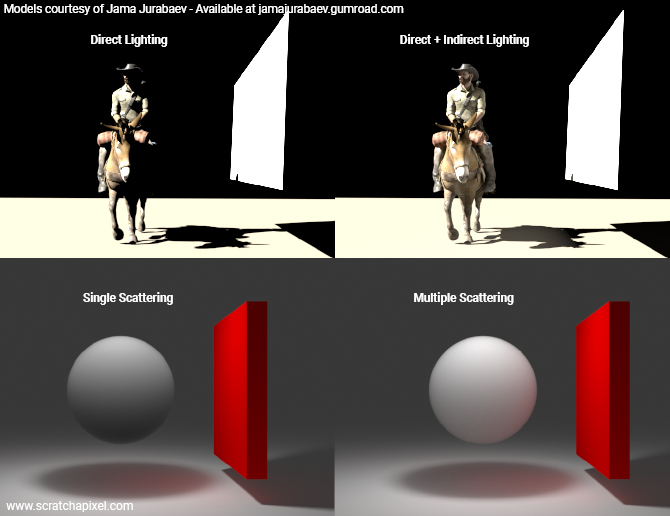

In a way, you can compare ray-marching to direct lighting. Direct lighting is better than no lighting at all (obviously) but certainly not as good as a scene rendered with direct and indirect lighting. With ray-marching, we are missing the indirect lighting part entirely. As the example below shows, indirect lighting is essential for creating photo-realistic images. Therefore the fact that the ray-marching algorithm cannot capture this effect is a big problem.

This has a concrete practical implication: you will have to pump a lot more light (as in creating additional light sources in the scene) into the volume to simulate the appearance of a cloud for example, and thus cheat rather than having the computer do the physical accurate and thus right thing. But then the question is: what is the alternative, how do get to - do - the right thing?

Stochastic-based or Tracking Methods

Well, the right thing is to let the computer simulate the way the photons do interact with the medium. In other words, simulate the photons' random walk behavior. This method aims to track the path of photons as they travel through the volume. This is why these methods are called tracking methods. This is not a "new" method. It was developed in the 1960s to simulate the radiation of particles such as neutrons for instance through plates. While versatile and very powerful this method is also very computationally expensive.

If you are interested to learn more about the topic on your own, search for Monte Carlo particle transport (MCPT) or Monte Carlo light or photon transport on the Internet. We won't go into the detail of this technique here. First, we are already providing a practical implementation of this method as an example of Monte Carlo simulation on this page: Monte Carlo Simulation. We also plan to write a lesson about it hopefully soon (2022). Check the Advanced 3D Rendering section for updates (the lesson should be called Volumetric Path Tracing).

Let's just say for now that the idea is to simulate the path of photons through the volume. The goal remains to solve the volume rendering equation:

$$L(s) = \int_{s'=0}^s T(s')\big[\sigma_s L_s(s') \big]ds' + T(s)L(0)$$Using Monte Carlo (see Mathematical Foundations of Monte Carlo Methods and Monte Carlo Methods in Practice to learn more about this topic). As with ray tracing, we will not do so by simulating and tracking the path of photons as they travel forward (from the light source to the viewer or sensor) but backward from the viewer to the light source. The path of a particle through the medium can be characterized by a series of steps taken by the photon where each step in that path is defined by a length and a direction. We will randomly sample the length of the direction of the photons to account for this behavior using essentially the knowledge we have about the medium itself, and notably its scattering and absorption coefficients as well as its phase function.

Stochastic-based methods for Monte Carlo simulation or integration are computationally expensive as mentioned earlier. Techniques such as delta tracking which you may have heard of can be used to improve the process (at the cost of adding complexity to the code). Delta tracking will be studied in the lesson devoted to volumetric path tracing as well.